Snell Family History & Genealogy

Snell Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

We don't have any information on the history of the Snell name. Have information to share?

Name Origin

We don't have any information on the origins of the Snell name. Have information to share?

Spellings & Pronunciations

We don't have any alternate spellings or pronunciation information on the Snell name. Have information to share?

Nationality & Ethnicity

We don't have any information on the nationality / ethnicity of the Snell name. Have information to share?

Famous People named Snell

Are there famous people from the Snell family? Share their story.

Early Snells

These are the earliest records we have of the Snell family.

Snell Family Members

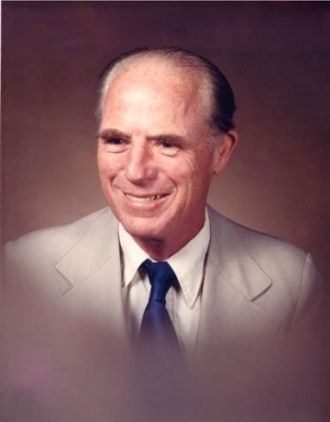

Snell Family Photos

Discover Snell family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Snell last name.

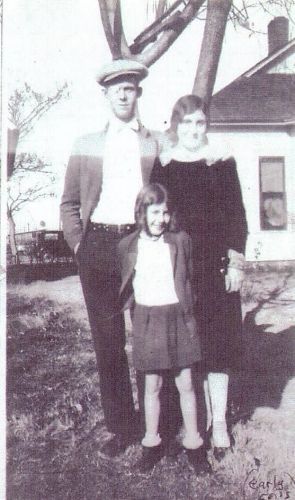

Richard and his wife are deceased, both are buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Lexington, NE.

Would like to return photo to her family. If you are related to her and want the photo, let me know. [contact link]

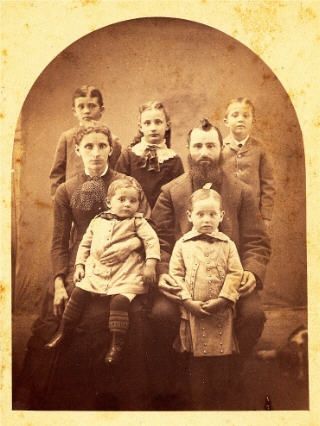

People in photo include: Benjamin Williamson, Jr.

People in photo include: Martin Dodson

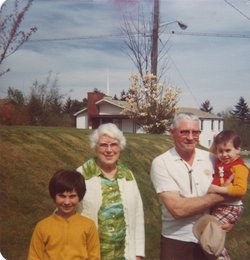

People in photo include: Janice Honor Snell

Snell Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Snell.

Updated Snell Biographies

Popular Snell Biographies

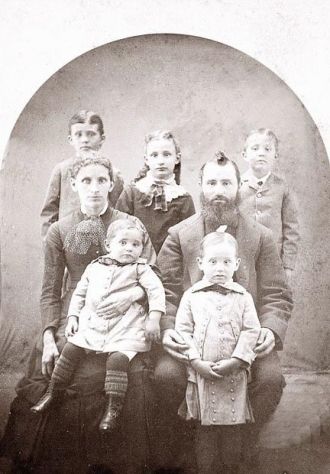

John George Snell was born to John William Snell and Sarah Ann Steen. He had seven siblings: Charles, Fanny, Ada, David, Angelina, Lucy, and James.

Snell Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Snell family member is 73.0 years old according to our database of 8,884 people with the last name Snell that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Snells

These are the longest-lived members of the Snell family on AncientFaces.

Other Snell Records

Share memories about your Snell family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Snell family.

Followers & Sources

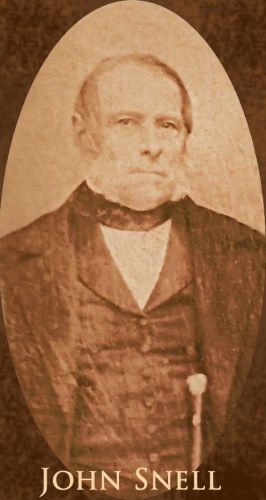

John Abner Snell – ever a controversial man – remains so to this day. During his lifetime, he achieved a mythological stature, at least within his family. His siblings would proudly describe themselves as the brothers or sisters of John Snell, “the famous missionary doctor.” His children revered him and considered him to be a “wonderful man.” Within the family and among many colleagues, he was considered to be “one of the most progressive and capable surgeons of modern times.” Many of his Chinese patients considered him to be nothing less than a miracle worker. Despite his many accomplishments, or possibly because of them, some fellow missionaries questioned his motives and ambitions and even wondered why he had become a missionary. John Snell was in the prime of his life; he seemed to be indomitable, but fate intervened. He died unexpectedly at age 55—many would say a martyr’s death.

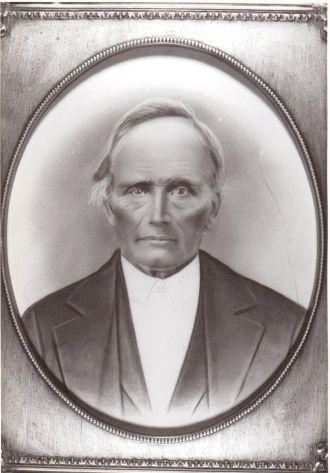

To try to understand this man of contradictions, it’s particularly useful to explore his immediate ancestors. John Abner Snell was likely named for his two grandfathers, John Snell and Abner Jarrett, and represented a unique amalgamation of two very different families. His paternal grandfather, John Snell, emigrated from Germany around 1836 as young man. During his exceptionally long life, he hop-scotched across the young nation, from New York, to Pennsylvania, to Wisconsin, and finally Minnesota. Brief accounts of his life indicate he was a proud, independent man who would rather die than ask for help.

John Snell’s youngest son, Leonidas, was the father of John Abner Snell. Throughout his life, Leonidas displayed a foot-loose independence similar to his father, routinely pulling up stakes and moving his family, usually prompted by some get-rich scheme. Charitably, he can be viewed as a visionary frontiersman. More realistically, he was an impetuous risk taker and poor money manager. His relationship with his family was often one of take-it-or-leave-it and his children invariably chose to take-it.

The family of John Abner Snell’s mother, Amy Jarrett, included early Dutch and English immigrants. Her maternal family settled in the colonies long before the Revolution and later descendents were among those who accompanied Daniel Boone across the Appalachian Mountains into Kentucky. A generation later, Amy’s ancestors moved on to west-central Indiana. Amy grew up near Crawfordsville, Indiana, a town known as the “Athens of Indiana.” Her family had strong fundamentalist roots and her guardian was a famous frontier preacher. While a teenager, Amy’s family moved from the relatively civilized region near Crawfordsville to McLeod County at the edge of the frontier in Minnesota. Amy was quiet and strong--she displayed her strength and determination not in her words, but in her actions.

The families of Leonidas Snell and Amy Jarrett were neighbors in McLeod County, Minnesota. The young couple married September 2, 1870 and soon moved to a small settlement near Duluth. Leonidas was likely drawn to opportunities associated with the booming lumber trade and federal lands available. John Abner was born in Knife Falls, Minnesota on October 28, 1880, the fifth of eight children. When John was around five, his parents made the long trek from Minnesota to central Florida, then a swampy, insect-infested frontier. One result of this move was that John considered himself to be a southerner.

It was John’s mother, Amy Jarrett, who insisted her children obtain the best education possible. She felt so strongly about the importance a college education that she left her husband sometime in the late 1890s and took her boys to Nashville where college was more readily available. To support her family, Amy truck-farmed, baked and then sold her goods at market. She was the primary breadwinner for the family although everyone was expected to work and contribute. Amy remained in Nashville until around 1916 when her children had all completed their educations. Only then did she return to Leonidas in south Florida.

Sometime before college, John crystallized one of his fundamental life goals--to achieve financial security. This drive to succeed financially was surely a reaction to his own his humble and unstable childhood. From his father, he developed an eye for money-making opportunities. Probably more important, he observed the example of his mother and learned that anything was possible if one was willing to sacrifice and work the hours required. Higher education became a means to achieve his financial independence.

Nineteen-year-old John Abner entered Emery College in 1899. It was at Emory that John accepted the second life-goal that would guide him--he “came to know the Master Physician intimately and the rich vital religious experience which he enjoyed so transformed him that he offered himself unreservedly for life-service on the mission field.” At home, John had received a solid Methodist upbringing and at Emory, he dedicated himself to missions. He was active in the Student Volunteer Movement, an organization that promoted foreign missions among the young, educated Protestants at the turn of the century. The movement combined religious fervor and a last wave of the frontier spirit to attract to inspire its members. Missions were established in China and elsewhere with a belief that “heathens” would be won over to Christ if they experienced Western thought through preaching, education, and medicine.

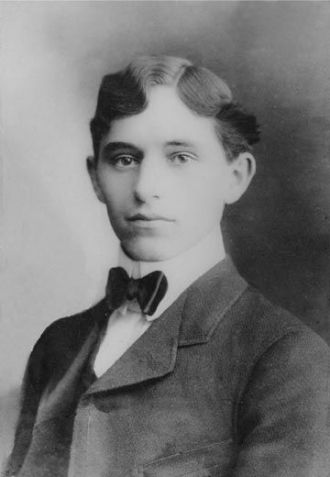

John transferred to Peabody College after his first year and completed his undergraduate education in 1903. Numerous studio photographs from this period show John fashionably dressed, even though his finances were always tight. One photograph includes him as a member of a basketball team, possibly the precursor to his lifelong advocacy for physical exercise. Despite his humble and chaotic beginnings, John Abner had completed the first important step of his career.

During his junior year at Peabody, he met his future wife, Grace Evelyn Birkett, who was also a student. Grace recalled her first impression of John, “a fine looking young man [with] handsome brown eyes and curly hair.” The couple became engaged on Thanksgiving Day, 1902. Soon after completing his undergraduate degree, John left for California for two years to teach school and earn money to help support his mother and younger brothers. Little is known of this period, except that many love letters were exchanged between the two which kept the romance alive. John returned to Nashville in 1905 and debated whether “he ought to be a minister or a doctor.” He decided to become a doctor “feeling there was a greater need for doctors and that his life would count for more.” He pursued this theme of practical Christianity all his life and encouraged his children to do likewise.

John entered Vanderbilt Medical College in 1907 and he and Grace were married on November 1, 1907 by Grace’s brother-in-law, James (Jim) Clarke. Financially, the couple’s first years were extremely difficult, but with sacrifice, hard work, help from family, and “God’s intervention,” they made it. John graduated from Vanderbilt in 1908 and moved to New York City for his internship.

In January, 1909, with his brief internship completed, John and Grace departed for Soochow, China, their first and only mission assignment. Soon arriving in Soochow, John received his Chinese name, Soo E-sang. While still learning the basics of the language, Dr. Parks, the founder of the hospital, left for a one year furlough. The young doctor now found himself in charge. The cottage hospital, established in 1883, was quite simple and primitive by western standards. Grace wrote that “the rooms were barely furnished, not even mattresses on the beds. The patients brought their own bedding and their own kin took care of them.” John welcomed the challenge, although his early letters home asked for his family’s prayers. John and Grace would spend the next twenty-eight years working and building the hospital.

When Dr. Parks returned from furlough, the two doctors split the duties with John assuming responsibility for surgery and general administration. In 1920, John obtained financing from the Rockefeller Foundation to replace and expand the hospital. The new hospital, completed in 1922, incorporated the very latest medical technology and even had air conditioning in the operating room. In 1927, Dr. Parks died and John became the chief administrator and surgeon for the hospital. During his many years of practice, Dr. Snell earned the respect and admiration of both his patients and colleagues.

In addition to his hospital duties, John found time to conduct many scientific and public health investigations. Among these, he assisted in discovering the snail which acts as the intermediate host of the oriental blood fluke, a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. He also promoted an anti-tuberculosis campaign. He was a frequent contributor to professional journals, sharing his experiences. In 1933, he participated in a survey of all the hospitals of China for the Chinese Medical Association. John wrote a fitness manual encouraging others, particularly sedentary missionaries, to do regular exercise. One of his colleagues described him as a “vigorous and commanding personality in keeping with his strong physique.”

John always enjoyed the new and innovative, whether in the hospital or at home. From his early days in Nashville, he owned cameras and many quality photographs survive. He later was one of the first to take home movies. Around 1920, John oversaw the building of a new home. The home was furnished with local furniture supplemented by occasional shipments from Montgomery Wards. Architecturally, the house is an imposing structure, but it lacks landscaping and elements that would make it attractive. Inside though, the house featured electricity, central heat, running water, and the first flush toilet in the city.

John’s primary outside interest—one he shared with many missionaries—was to get away to the Chinese countryside. He was an avid deer and duck hunter and always kept a hunting dog of some sort. One of his closest friends and colleagues, Dr. Fred Manget, felt that John drew “strength for his tasks and [the] courage to carry on through difficulties . . . from these times spent apart with Nature.” Hunting trips were also times when he taught his sons to be men. The tiger hunt arranged for his oldest son, John Raymond (always known as Raymond), was clearly designed to test his son and expecting success, to establish him as a man. In a similar way, he and his youngest son Fred shared a common interest in spiders and spent many hours together in the field.

Throughout his life, John was driven by his twin goals of achieving financial well-being and providing missionary service. Early on, he decided he needed to supplement his missionary stipend to provide financial security and to insure his children would have opportunities for college. John was an opportunist, not unlike his father. He turned his hobby of collecting Chinese coins into a small business, buying and selling coins. Around 1920, when construction of the new hospital was about to begin, he bought and refurbished a brick factory to produce high quality bricks for the hospital. Later, around 1933, he responded to a need for fresh milk by setting-up the first dairy in the Soochow. All of his outside endeavors were accomplished while maintaining a heavy hospital work load.

Some of his missionary contemporaries considered his two goals to be in conflict, but John believed if he could accomplish both without compromising his missionary duties, that was his business. One can still sense the ruffled feathers in the missionary community which described the “outstanding characteristics of Dr. Snell [are] vigor, energy, persistence, and an entire indifference to any convention that might stand in the way of what he considered a right and worthy course of action.” This description, printed in The China Christian Advocate, reported that more than one “member of the mission has said to another member that it was difficult to square Snell’s brick factory and dairy with the mission rule against engaging in outside enterprises. The invariable reply, which invariably was granted, was that Snell did a full sized man’s job as a missionary doctor, and that the time and strength he gave to these other enterprises were no more than others devoted to recreation.”

Much of what we know of John’s family life comes from the autobiography of Grace. She was responsible for the day-to-day raising of their seven children. John recognized he short-changed his family. In a lengthy letter to his children written while on a ship to Japan to buy cows for his dairy, he cautioned “This is a much longer letter than I had intended to write and longer than I will write for a long time to come. For at home, I do not have the time to spare; there is always something waiting to be done.” Despite his busy schedule, he did stay connected to his children and was a dominant force in shaping their lives. He wrote letters to his children marking important events like birthdays and going away to college. He encouraged his children to set high goals, to find their true calling, and to dedicate themselves to their work.

Once every seven years (1916, 1923, 1931), the family returned to the states for furlough. During these periods, John set a hectic pace. He used these times to update his medical skills, to learn new procedures, and to purchase the latest equipment for his hospital. The visits were also packed with visits to widespread relatives. During these visits, he also shared his love of the outdoors--of adventure and risk-taking--by visiting all the major national parks in the west. Mixed in with the home-visits were efforts to make a little money, often with limited success.

As he grew older, John simplified his religious philosophy—he seems to have accepted the tenant from the hymn, They’ll Know We Are Christians by Our Love. His oldest son Raymond remembered his father’s teaching, “The two greatest things in life are to be guided by God and to love your fellow man.” In his last letter to Raymond written two weeks before the onset of an unexpected illness that proved fatal, he shared his desire for perfect love. In what he referred to as a small “dissertation,” he explained how love provides the understanding needed for ongoing relationships: “When LOVE becomes perfect in this world, won’t we all be able to read the other fellow’s mind and see his thoughts.”

On his deathbed, he dictated a set of notes to his daughter Dorothy. The first dealt with various family financial matters. When he finished with these, he then left a message for his children:

“l want you to know . . . that if I could live my life over I would give it to China. But I would fill it full of love. What China needs is love—and Christianity is love. There can be nothing happier than a life whose first purpose is to demonstrate Christian love through service.

If I could live again, I would go out on the canals and footpaths of the countryside and take beyond the walls of this hospital the great message of love that lives in this work. China needs all of it that she can get. Will you tell them this, Dorothy? Tell them that this is the GOOD life.”

Death came quickly and many lengthy obituaries and tributes were printed in China and in the States. The following tribute describes John Abner Snell’s last hours:

“On March 2, 1936, Soochow Hospital and the Methodist Mission suffered an irreparable loss in the death of Dr. John A. Snell. On Monday, February 24, he had half a dozen operations scheduled. After the first he had to call for a chair and rest a few minutes. In spite of a temperature of 102, he drove through with the second. The next morning he was removed to the hospital and a fight began for his life, the local doctors calling in their colleagues from Huchow and Chanchow Hospitals of the same mission. But all efforts to save his life were in vain.

The cemetery chapel was far too small to hold the throng that gathered to pay a last tribute to a man whose surgical skill had saved many of their lives. Conspicuous among those was a retired high official of the late Peking Government, who sat with the sorrowing family. Some years ago Dr Snell removed the cause of his trouble when his Chinese doctors had given him up to die, and to ensure his recovery gave him several transfusions of his own blood. Ever since he has not ceased to give evidence of holding Snell to be a blood-brother in every sense of the term.”

The death of Dr. Snell left a huge vacuum. His family, friends, and colleagues all asked in disbelief, “Is Dr. Snell dead? What will we do? Is Soo E-sang dead? How can that be.”

In her autobiography, Grace Snell wrote of her husband’s life. “John was a wonderful man, strong in body and mind, an exceptional doctor and an especially fine surgeon. He was loved by all the foreigners and Chinese alike. He had many perplexing problems, but he was always able to see them through.” It is a worthy tribute but noticeably absent is any mention of his role as a father or husband. Grace typically omitted or glossed the difficult times.

Financially, his unexpected death and the political turmoil in China left his family in difficult straights. Most of his savings were tied up in his brick factory and the dairy. Without his stewardship and with the political and military chaos in China in the late 1930s, the investments soon became worthless. The mission board continued to support his wife and children at a modest level.

The lasting legacy of John Snell was the example and inspiration he passed on to his children. In 1994, Soochow Hospital celebrated its 110th anniversary. Two of John Abner’s sons, Raymond and Fred, attended as honored guests to the official ceremony. The memorial book commemorating the anniversary recognized John Abner Snell as a previous administrator, but with little comment. It omits his role of expanding and transforming the hospital and his twenty-eight years of service. This omission is regrettable, but not surprising since the Communist government routinely rejects any positive western influences.

John Abner Snell was not a perfect man--virtue is an elusive quality defined by each observer. A determined man may be viewed by some as stubborn and hardheaded; a visionary as radical; a self-assured man as proud; a risk-taker as foolish. Often the difference is slight: a viewer’s own experience, an invisible line crossed, a different time and place. But John Abner Snell did make a difference, a positive difference, and if others need to judge him, he would want them to base their assessment on the positive difference he made.

Updated: March 15, 2004