Bensaeid Family History & Genealogy

Bensaeid Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

We don't have any information on the history of the Bensaeid name. Have information to share?

Name Origin

We don't have any information on the origins of the Bensaeid name. Have information to share?

Spellings & Pronunciations

We don't have any alternate spellings or pronunciation information on the Bensaeid name. Have information to share?

Nationality & Ethnicity

We don't have any information on the nationality / ethnicity of the Bensaeid name. Have information to share?

Famous People named Bensaeid

Are there famous people from the Bensaeid family? Share their story.

Early Bensaeids

These are the earliest records we have of the Bensaeid family.

Bensaeid Family Members

Bensaeid Family Photos

Discover Bensaeid family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Bensaeid last name.

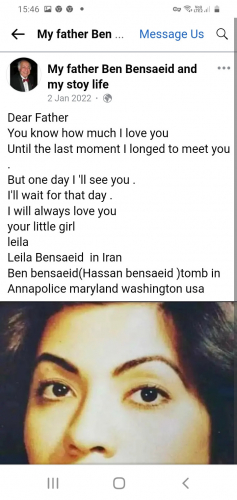

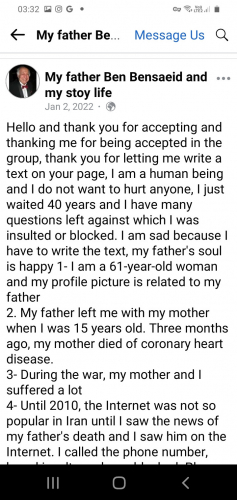

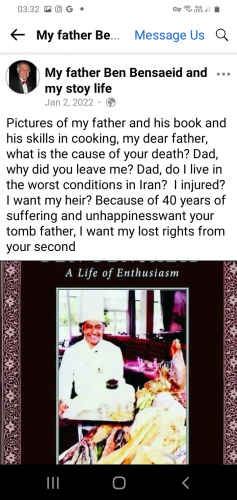

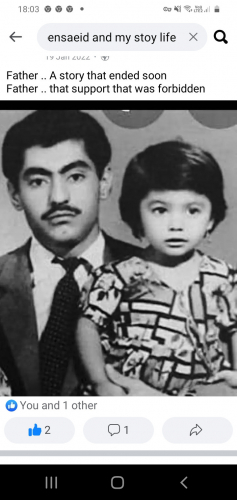

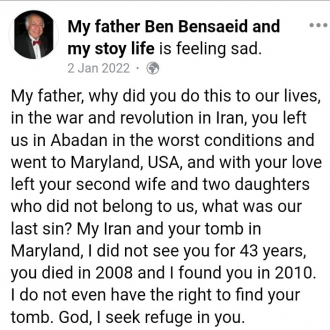

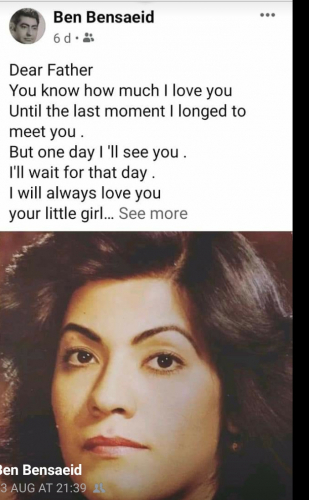

Leila bensaeid the true daughter of ben bensaei

Touching ‘I Love You Mom’ Messages For Mother’s Day

“I don’t say it nearly enough, but I want you to know that I love you, Mom. Thank you for everything that you do for me. I know that it’s not always easy being a mom, but you make it look effortless. You are amazing and I am so grateful to have you in my life. Happy Mother’s Day!”

“To the woman who made all my dreams come true, Mom, I love you with every single beat of my heart. Without your constant love and support, I would never be where I am today. Thank you for everything, Mom. I love you from the bottom of my heart. Happy Mother’s Day!”

“I love you, Mom. You are the brightest light in my life and you always make me feel like everything is going to be alright. No matter what life throws my way, I know that I can always count on you to be there for me. I am so grateful to have you in my life. Happy Mother’s Day!”

“The highest compliment anyone can give me, Mom, is to say that I’m like you. That means more to me than anything else. Because being like you means that I am strong, loving, caring, and most importantly, I am a good person. Thank you for being such an amazing role model, Mom. I love you from the bottom of my heart. Happy Mother’s Day!”

“There are so many things that I want to say to you, Mom, but ‘I love you’ will always be the most important. Because no matter what life throws my way, your love is always there to catch me. You are my best friend and I am so grateful to have you in my life. Thank you for everything, Mom. I love you from the bottom of my heart. Happy Mother’s Day!”

“I am so lucky to have you as my mom, because I know that no matter what happens in life, you will always be there for me. You have always been my rock, Mom, and I am so grateful to have you in my life. Thank you for everything that you do for me. I love you from the bottom of my heart. Happy Mother’s Day!”

Short ‘I Love You Mom’ Messages to Send Your Mom

“Love you mom! You’re my best friend and I can’t thank you enough for everything.”

“The least I could do is offer a shoulder to cry on and a box of donuts… because that’s what mom’s do! Love you, Mom!”

“The best thing in world is having you as my mom! I love you so much.”

“The best part of waking up is realizes I get to spend another day with my amazing mom.”

“No matter how old I get, I’ll always be your baby girl. Thank you for everything, Mom. I love you!”

“Words cannot describe how grateful I am for you, mom. I love you from the bottom of my heart.”

“The best kind of love is the kind that doesn’t keep score. I love you mom!”

“No matter where I am in the world, I’ll always choose you, mom.”

“I don’t say it enough, but I love you Mom! Thank you for everything .”

Short ‘I Love You Mom’ & Love of a Mother Quotes

“There’s no place like home… and no one like Mom.”

“I am who I am because of you, Mom. Thank you.”

“The heart of a home is a mother whose love is warm and strong.”

“My mom is my best friend, my shoulder to cry on, and the one person I know I can count on no matter what.”

“There’s no other love like a mother’s love, and nobody knows that better than me.”

“A mother always has to think twice, once for herself and once for her child.”

“I realized when you look at your mother, you are looking at the purest love you will ever know.”

“A mother is a person who seeing there are only four pieces of pie for five people, promptly announces she never did care much for pie.”

“All that I am or ever hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.”

“There’s no way to be a perfect mother and a million ways to be a good one.”

“Being a full-time mother is one of the highest salaried jobs… since the payment is pure love.”

“The more a daughter knows the details of her mother’s life — without flinching or whining — the stronger the daughter.”

“There’s only one pretty child in the world, and every mother has it.”

“Most mothers are instinctive philosophers.”

“A mother is not a person to lean on, but a person to make leaning unnecessary.”

“My mother used to tell me that paradise is a place without mothers.”

“The biggest love story is the one you have with your mom. Pure, selfless, and infinitely forgiving.”

No matter what life throws at me, I know I can always count on my mom for a hug and a home-cooked meal.

“Mom, the way you love me is something I can only hope to give to my children someday. Your capacity for love is endless, and I am so grateful.”

‘Love of a Mother Quotes & Sayings’

“A mother’s love is deep and strong, it touches the heart and lasts forever.”

“Mother’s love outlives everything.”

“A mother’s love for her child is like nothing else in the world.”

“A mother’s love liberates.”

“There is no other love like a mother’s love for her child.”

“Mother’s love grows by giving.”

“Youth fades, love droops, the leaves of friendship fall; A mother’s secret hope outlives them all.”

“No language can express the power and beauty and heroism of a mother’s love.”

“A mother’s love is never-ending and will always be there no matter what the circumstances are. It is a force that cannot be stopped or denied. It is the one thing that can always be relied on.

"The Lord opens the eyes of the blind; The Lord raises those who are bowed down; The Lord loves the righteous." (Psalm 146:8)

Today's Bible verse is full of promises from God. He sees the oppression of people, and God brings justice. When people are oppressed, they can feel invisible, and people think they can get away with injustice because they are unseen. But, God sees.

God gives us both physically and spiritually. God sets us free from physical, emotional, and spiritual strongholds.

God sees every act of kindness, as well as every injustice. God executes both justice and reward. We may not see justice quick enough, but we can be sure it is coming unless there is a change of heart. Thankfully, God is merciful and will extend mercy to those who turn and offer Him their hearts.

We wonder why anyone would trust the world's power when we know the power of God… But we do. God is greater than the tangible power-holders in the world.

The world attempts to blind us from hope. They shut God out of everything and try to hush Him from our lives. The enemy hides the world in darkness and blinds the unbelieving from seeing Jesus.

God is able to give sight. Jesus is the One who opens the eyes of the blind and gives spiritual sight to understand His Truth. We need to stop falling for the mistaken idea that God does not see us. When we make Jesus the Lord of our lives, He becomes our righteousness through our faith.

We were made in God's image, but through sin, we have lost our identity. Jesus restores that identity through His act of love for us on the cross at Calvary. Jesus is our hope of salvation – removing our sin and becoming our righteousness so we can have a relationship with God.

No doubt about it. Jesus is Lord. He is involved in the lives of God's people and His creation. He is the One who opens our spiritual eyes.

When will we recognize that God is greater than the tangible power-holders of our world?

Heavenly Father, You are the one that is involved in the lives of Your people and Your creation. You are the One who opens my spiritual eyes. You are the one who sees and is aware of my needs, and You love me. In Jesus’ name, Amen.

Bensaeid Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Bensaeid.

Updated Bensaeid Biographies

Popular Bensaeid Biographies

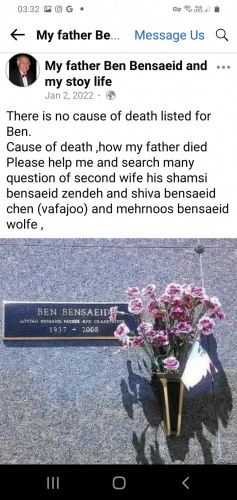

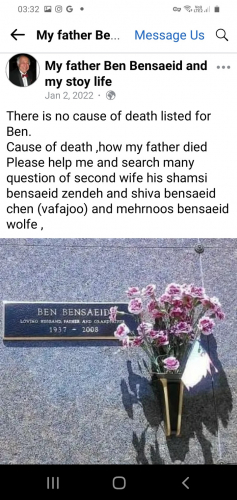

Bensaeid Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Bensaeid family member is 71.0 years old according to our database of 1 people with the last name Bensaeid that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Bensaeids

These are the longest-lived members of the Bensaeid family on AncientFaces.

Other Bensaeid Records

Share memories about your Bensaeid family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Bensaeid family.

Leila Bensaeid

Leila Bensaeid  Leila Bensaeid

Leila Bensaeid  Leila Bensaeid

Leila Bensaeid The Land

To find my father’s grave, first quiet your mind. Walk slowly. Look up. You will see trees waving their welcome, birds rejoicing in their branches as you pass tangent to their lives. You will see unfazed sky, blue as eyes or cotton clouds, or at night, stars untarnished by city lights. The daylight is mediated by a thousand leaves, casting a warm halo over everything in autumn and green shade in summer. In winter, the crispness will astound; you will think you have just put on glasses after not realizing you had needed them.

Breathe in, and show your lungs what air once felt like. Breathe out, become the breeze around you, and know you are about to be inhaled by the trees. Look down. In a single square inch, there may be a thousand creatures. There may be a turtle lumbering across the path, or a gaggle of baby turkeys chasing their mother or grass scheming skyward, or a quiet blanket of pine needles.

If the path has not been mowed for some time, which it probably hasn’t now that my father is gone, you may be wading through waist-deep grass, and you will need to retain only what is healthy about your fear of snakes and biting bugs. If you let them, your animal instincts will work, rusty as they may be from the dulling of modern life. Tread slowly and quietly, and you will see more of the life that is bustling all around you; you will begin to feel your own heartbeat and the heartbeats of other things. But as you go quietly, wear orange—hunters stray onto this land, and you would not want to be mistaken for a deer.

At the end of the driveway, on your left you will pass a ruin of a house that has been falling down for three decades. Some seasons, vulture families nest there, wheeling above you in the blue of the day, a slow and circling reminder that death is necessary for life. In the evenings, they crouch on the crumbling chimney and rotting rafters, watching you as you make a fire in the ring of stones about 20 paces from the house. You may wonder to yourself what they watch when humans are not there making fires, and then remind yourself that animals do not need humans to make meaning of their lives.

JoeFail-JoeAndKatherine2.jpg

Katherine and her father.

Cindy

On your right, you’ll see a white trailer with a black tarpaper roof and a decaying plywood porch. This, and the vulture house, are relics of the former owner of this land, who died of ovarian cancer in her early 30s and left her 250 acres to her friend, my mother, because she trusted her to leave it wild. Cindy lived alone here with her cats and goats, which went feral after her death, the goats wreaking havoc on the house and the cats disappearing into the woods.

My family came on odd weekends, my parents doing what upkeep they could, and my sister and I whining about the lack of creature comforts while, unbeknownst to us, learning a love of nature that would endure throughout our lives. In the years following Cindy’s death, we would catch glimpses of Teresa—her favorite cat, shorthaired and calico-camouflaged—at the edge of the woods, her golden eyes glinting with both accustomed wildness and the memory of being tame. She would crouch at the fringes of our frolic, never close enough to touch, sometimes suspiciously devouring the food we would leave for her, but always retreating back into the woods.

I was fascinated by her. What must it have been like to live the two halves of her life in such different worlds? To sit on laps and sleep in beds and then be forced to fend for herself? Did she feel abandoned or freed? Did she think about her past life, or live only in the present, stalking the next field mouse or evading the next fox? We saw her less and less frequently, as the portion of her life as a wild cat grew greater, until eventually we stopped seeing her at all. I have often wondered about the end of her life, where and when and how she came finally to rest and what it was like to be so utterly alone—probably the only one of her species, wild in that vast wilderness, with memories of a different, distant time. And although her circumstances had changed so radically, she held on to her home, attached, whether wild or tame, to the land where she was born.

Cindy herself is not buried on the property, and wasn’t able to live out her last days there as she had hoped. She had flown alone to Hawaii for an experimental cancer treatment, and, very ill, died in Los Angeles on the journey home. Her family was less than thrilled that she had left her land to us instead of them and proceeded to punish her by violating all her last wishes, suing my parents and making their own plans for Cindy’s remains. She had wanted to be buried naturally and laid to rest in her woods, but instead she lies embalmed in a treeless, fake-flowered cemetery, ornately headstoned—Elbert County, the “granite capital of the world,” is fond of headstones.

My father knew for many years that he wanted to be buried “on the farm”—not in a cemetery, not in a casket, not embalmed—just his body in the earth at a spot in the woods of his heart’s choosing.

Cindy’s father had bought hundreds of acres near the Savannah River just before it was dammed to form Lake Richard B. Russell. Surrounding land was going cheap as owners sold fast to avoid the floodwaters. In the end, not as much land was flooded as had been feared, and Cindy and her siblings each inherited several hundred lakeside acres from their father. When my parents inherited Cindy’s land, they also inherited years of unpaid interest and penalties to the IRS. But my parents knew that seldom do such riches get handed to us in this world. They paid the taxes, sold small peripheral portions to clear the debts and protected the rest under a conservation easement, which will do its best to keep the land undeveloped in perpetuity, aside from one house and a few additional structures. The land is bordered on each side by beautiful creeks, in which we often found arrowheads and Indian pottery when we played as children.

The House

Early on, my parents settled on a dream of retiring there someday, and for 25 years, though they lived full time in Athens and then in Charlotte, NC, where my father was a biology professor, they would go to Elberton every chance they got. For years, we would sleep in Cindy’s increasingly decrepit trailer, which was understandably a refuge for various and sundry vermin whenever we were not there, and those creatures weren’t keen to give up their stronghold when we visited. My parents wanted to build a house for themselves on the property someday, but in 1994, nine years after inheriting the land from Cindy, an opportunity of a different sort presented itself.

On Highway 72 between Elberton and Athens, they noticed an old farmhouse with a “For Sale” sign out front—a dignified, single-story, high-ceilinged hardwood house that you knew was built long before the highway ran parallel to its porch—a highway which was being widened, and the house would be torn down no matter what. So my parents asked if they could have the house without the land, with the plan to have it cut in half and moved to Elberton. The family, I’m sure, thought my parents were more than a little nuts, but they loved the thought of their beloved home not being razed to the ground, so for $500 plus the costs of the move, my parents bought themselves a house.

They chose a spot at the top of a wide meadow, not far from Cindy’s trailer, built a foundation, and moved the house in halves, on two large flatbeds whose “Wide Load” signs were the understatement of 1994. They sealed up the house’s scar and put on a new tin roof to protect it from the elements, and then set it aside as a Project for Later When We Have the Money.

We still used the house, unfinished, in the interim. As the trailer sank into greater disrepair, we slept instead on the wraparound porch of the house, spreading out old futons in the open air. We’d have adventurous family Thanksgivings there (would the ancient oven in Cindy’s trailer hang on long enough to cook a turkey?), and my dad would bring his ecology classes down from Charlotte for field studies. He taught at a historically black university, and for many of his urban students, these trips were their first exposure to true nature. For almost a year, a poet friend of ours camped on that porch, working on his poetry, walking to nearby Lake Russell to fish and learning how to be alone.

JoeFail-Burying.jpg

His family buried Joe in the woods in accordance with his wishes.

The Grave

My father knew for many years that he wanted to be buried “on the farm”—not in a cemetery, not in a casket, not embalmed—just his body in the earth at a spot in the woods of his heart’s choosing, although the exact spot was always yet-to-be-determined. When he and my mother first wrote their wills, I was maybe 10 years old. I neither wanted to nor really could conceive of the necessity of those documents, and I remember my father trying to describe to me his burial wishes as I stuck my fingers in my ears and sang “Mary Had a Little Lamb” to drown him out. To listen would have been to acknowledge not only his mortality, but that of both my parents, of everyone we knew and ultimately of myself.

My parents did their research, making sure it was, indeed, legal to bury a body on private property, (In general it is, if you are the property owner and the land is not within city limits.) They filed the wills away in a fireproof box in the bottom of my mother’s closet, along with immunization records, birth certificates, Social Security cards and expired passports, and covered it in a pile of winter socks. And nothing more was said for 20 years, during which time they paid off their city house and then turned their efforts to the renovation of the old Elberton farmhouse, which had waited its turn patiently for decades.

The house was a month from finished when my father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given less than a year to live. At the age of 66, he walked around the land, which he called Cinderella Farm (after Cindy), looking for the spot that felt right. He found it at a bend in the path that circumscribes the meadow, beneath the quiet trees. And when he told me about it, I willed myself not to stick my fingers in my ears and sing at the top of my lungs.

He used to say, ‘Trees have infinite patience.’

Diagnosed in January, my father survived to see one final spring at Elberton, still teaching at the university and going down to Georgia whenever he could. Each weekend he was weaker, but still we walked the land in sections, trying to learn things that he alone among the living knew—where the boundary lines were, how to navigate the pathless woods, where to mow to keep fire lanes traversable. As we walked, he would name the trees—beech, red and white oak, tulip poplar and longleaf pine. I learned that beeches love creeksides and are “tardily deciduous,” meaning that, though their leaves turn brittle and brown, they do not shed them in autumn with all the other trees, but keep them on, like clothes, for the winter. Their branches also end in sharp points, which if they poke you can make you exclaim “son of a beech!”—a mnemonic that always roused a laugh from his students. I learned that his favorite tree was the white oak, quercus alba, a monolith with a towering canopy and leaves like sculpted hands, flat and forward reaching. The scientific names of all oaks start with quercus; alba means “white” in Latin, but it means “dawn” in Spanish, a language my dad spent his whole life trying—and largely failing—to learn. He used to say, “trees have infinite patience,” and I am sure, though he didn’t want to have to leave our world so soon, that he was deeply fascinated—even, as his body failed him further, looking forward to becoming a tree.

The last time he was in Elberton was the weekend of his 67th birthday. Mostly too weak to walk, he rode while we drove him where we could around the land, and at night he dozed while we worked an impossible thousand-piece puzzle of Gustav Klimt’s painting “The Tree of Life.” Three weeks later, he died at home in North Carolina, with us by his side. My father died at 2 a.m. on May 30th in Charlotte, and by 2 p.m. we had buried him in Elberton. Overnight, hospice came to write the death certificate, and we dressed him in his favorite clothes—sweatpants, sweatshirt, wooly socks, a hand-knitted hat my mother made, a scarf I knitted him when I was 13, with blue and red stripes in Fibonacci sequence—and his glasses, which he was always looking for.

The only interaction with the funeral industry we had was for the transport of the body, a job performed by two lovely and respectful men from the Carolina Mortuary Transportation Service, who I’m guessing had never had a job quite like this one. They didn’t question my family’s wishes, though they seemed relieved to hear that my uncle was digging the grave with a backhoe—it wouldn’t just be several grief-stunned women with shovels. My mother had called several different companies to try to line up the transportation of the body in the days before my father’s death. The others were overtly rude to her, refused to do the job and even told her it was illegal, which she knew wasn’t true.

My father had marked his potential grave sites with pink plastic ties on nearby trees. There were several contenders, but the one settled on was perfect—watched over by a centuries-old white oak, its canopy a comfort in any weather, and its branches the certain home of many other creatures. My uncle had to break through granite slabs and tree roots to dig deep enough—Georgia clay does not offer itself easily. We carried my father to the grave on a handmade pallet, wrapped in a sheet that seemed to give off its own light in the new summer sun. We lowered him into the earth. We read a few poems—I chose Tennyson’s “Ulysses”: “Come, my friends, / ‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.”

We read a letter from a friend and fellow teacher written to him on the day before he died: “Please know that you will never be far away. With every tree, I will see my young pre-school students using shovels, digging holes, planting trees on the campus of JCSU. Because of you… An old tree log is a magnificent mountain of decomposition, a sustainer of life, a road back to the earth… A road you must now travel.”

As we all took turns covering him with the earth that he so loved, as much as I could not fathom that I was burying my father, I was amazed and comforted, thinking of that still-green root that was cut to dig the grave—already it would be striving forward, nothing between it and my father but a cotton sheet, white as angels; white as oak. The root would, we knew, heal itself by growing, quickening the process by which my father became the quercus alba, oak of the dawn, that sheltered us all.

In the diary he kept on a trip to Europe just before his diagnosis, it’s clear my father knew something was wrong—he had pain that kept him from eating and sleeping for much of the trip, and he wrote, before having seen any doctor, “this may be my last adventure.” His prescience haunts me, but on good days I know he adventures on. The white oak’s fuse burns forward through his body, and the worms work their way through the Fibonacci sequence of his scarf, learning that everything that has come before adds together to make what happens next. And the leaves of the tree above, on branches related to one another also by the ratio of the Fibonacci numbers, every day spin sugar from the sun.

JoeFail-JoeAndKatherine.jpg

The Rest

Past the falling-down house, past the decrepit trailer, past the magician’s assistant of a house sawn in half and now miraculously whole, continue down the path. Pause at the wild persimmon trees and see if they have any fruit—their flesh is soft and sweet, but their skin can numb your tongue with bitterness. Veer right when you have a choice—this used to be the road less traveled, but now it is trampled by pilgrims. Soon, on your left, you’ll see the small clearing under the oak, with the slight mound where wandering jew now grows. We’ve put a bench there, and a Navy footlocker with a photo album, a journal, an Audubon guide, his favorite book on Zen Buddhism. A friend with connections to Elbert County granite made us a small flat stone; the epitaph reads, “A friend of trees.”

Sit and stay awhile, till the birds forget you are foreign and shower you with song. This place rejuvenates; you will leave infused with what Dylan Thomas called “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.” When you are finished, retrace your steps. Stop and see the new-old house, beautiful and simple, its floors made from wood salvaged from its former self, with a single, slim, horizontal board running across the middle of the hallway, homage to where the two halves were joined. Wander its rooms, quiet with memories made and yet to be made. Wend your way back down the driveway, and prepare yourself for your return to the world.

If you drive through Elberton on your way out, you may pass the cemetery where Cindy rests, not as she wanted, but, I believe, happy at least in her choice of my parents as her successors. You may pass the land where the house once stood and notice that Highway 72 has never been widened. You may pass the Georgia Guidestones, a mysterious granite Stonehenge commissioned by an anonymous creator, inscribed in many languages with 10 precepts by which humanity should live. The last two are: “Prize truth—beauty—love—seeking harmony with the infinite” and, “Be not a cancer on the earth—Leave room for nature—Leave room for nature.”

As you drive, roll down the window, and feel the wind on your skin. Watch the red clay blur past, knowing now a bit better what it holds. Before you know it, you’ll be home.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism,I WANT ADRESS grave of my father ben bensaeid of shamsi zendehroudi and two her daughters mehrnoosh wolfe , of zionsville , and shiva chen of potomo falls

Leila Bensaeid

Leila Bensaeid My mother was a strong, happy and literate woman. Before my father worked in Shiraz, we had a good family, but after my father went to Shiraz, there was a long distance between them. But we no longer saw a father, no insurance, no legal war, and my brothers in the war, the injured, my father, and his two daughters in America with the best life, and me and us in the conditions bad life

Followers & Sources

the cry of life

It has not remained unanswered.