Thor Heyerdahl, Anthropologist and Adventurer, Is Dead at 87

By John Noble Wilford April 18, 2002

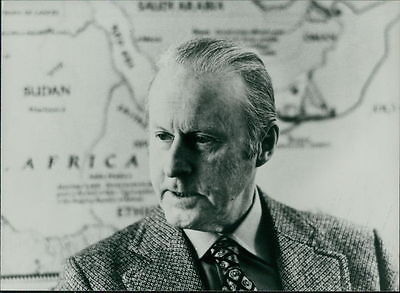

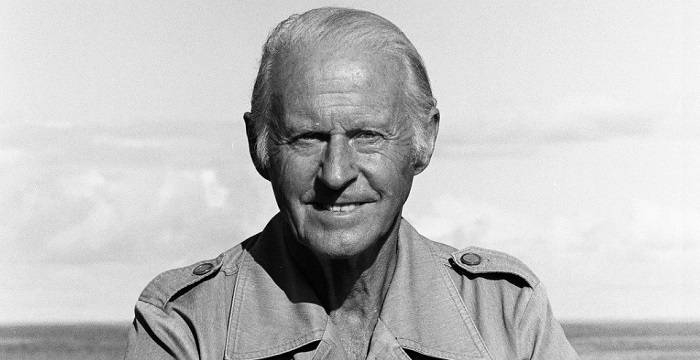

Thor Heyerdahl, the Norwegian anthropologist and adventurer who won acclaim navigating the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans to advance his controversial theories of ancient seafaring migrations, died yesterday.

Mr. Heyerdahl, who was 87, died of cancer in Italy, where he had been vacationing, the family said. He had lived in recent years in Guimar, Tenerife, in the Canary Islands.

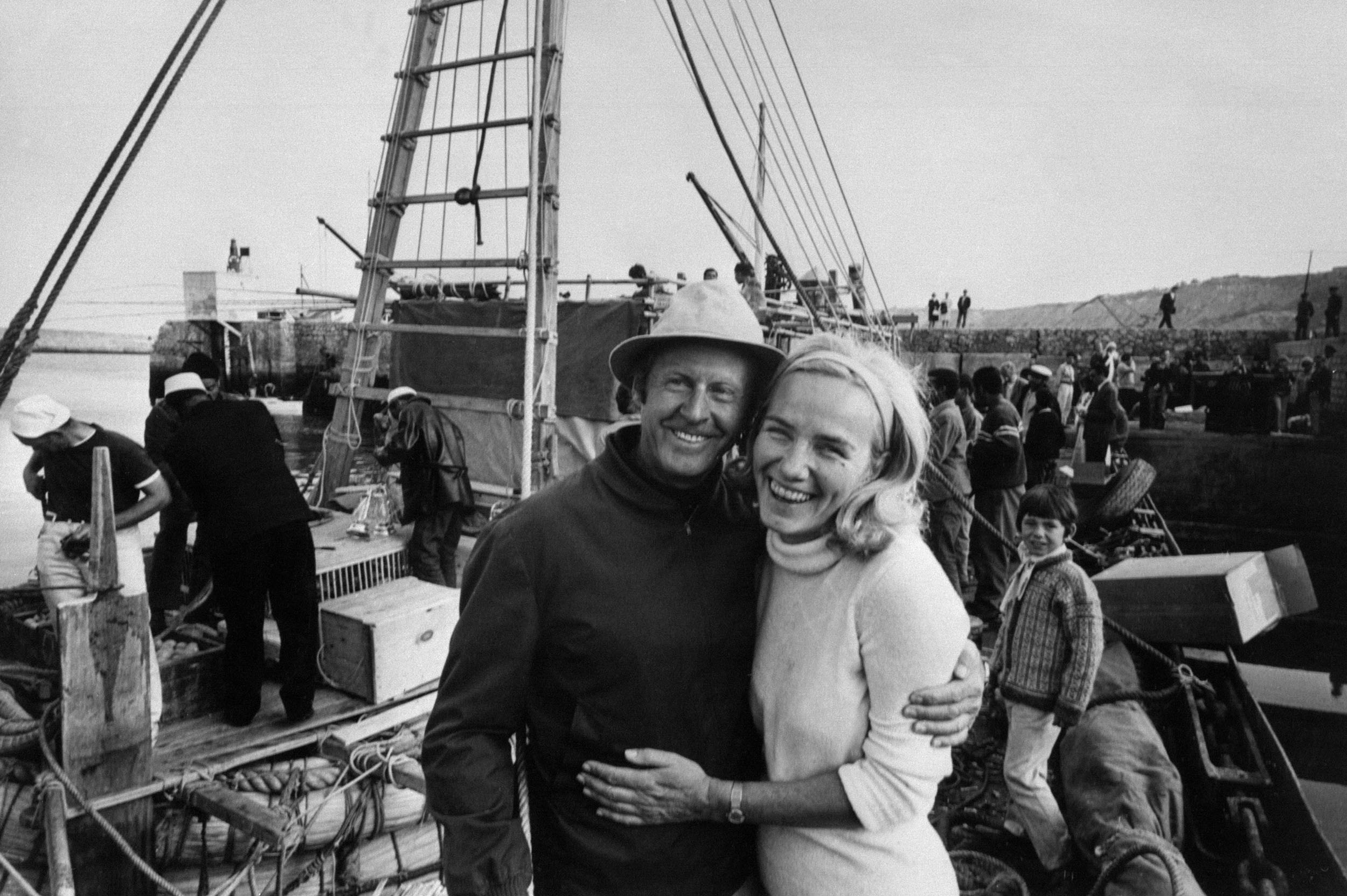

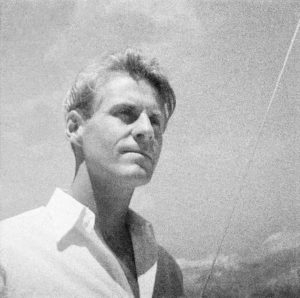

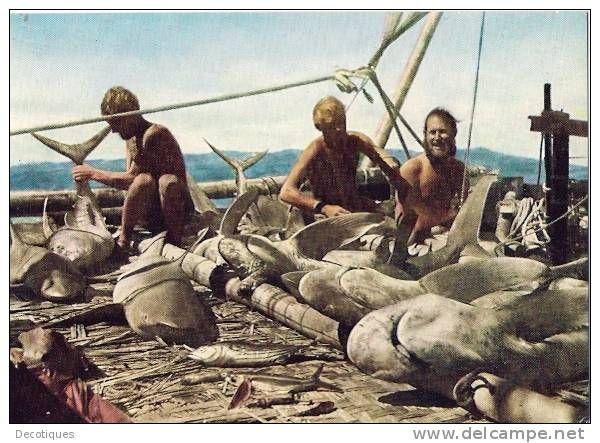

Fame came to Mr. Heyerdahl in 1947, at the age of 32. A tall, lean man in an appropriately Viking mold, he and five others crossed a broad stretch of the Pacific in the balsa-log raft Kon-Tiki, seeking to prove that the Polynesian islands could have been settled by prehistoric South American people.

The 101-day, 4,300-mile drifting voyage on the 40-square-foot raft, a replica of pre-Inca vessels, took them safely from Peru to Raroia, a coral island near Tahiti. This demonstrated to Mr. Heyerdahl's satisfaction that his theory could be fact. He was convinced that Polynesia's first settlers had come from South America, and not from Asia by way of western Pacific islands, as nearly all scholars thought.

Thor Heyerdahl was born Oct. 6, 1914, in Larvik, in southern Norway. He once noted that he did not share from birth the affinity for the sea that his Norwegian heritage and lifelong work might have presupposed.

"All my ancestors came from inland," he said in 1979. "I was dead scared of the water as a young man. If I had been a sailor, I would have believed that you couldn't cross the ocean in the Kon-Tiki. My ignorance was very lucky."

Young Thor's father owned a brewery and his mother was head of the local museum. It was her influence that led him to the study of nature and zoology. At the University of Oslo, he specialized in zoology and geography, but before graduating left on his first expedition to Polynesia, in 1937-38.

He went with his bride, Liv Coucheron Torp Heyerdahl (they were later divorced), "to spend a year living as Adam and Eve," as he wrote, on the island of Fatu Hiva in the Marquesas Islands. They lived there under primitive conditions, conducting research on the flora and fauna.

There he also began to contemplate the question of how the Pacific inhabitants reached these widely scattered islands. He came to believe that human settlers had arrived with the ocean currents from the west, just as much of the vegetation and animal life had done.

The time on Fatu Hiva — about which he was to publish a book, "Fatu-Hiva: Back to Nature," in 1974, and recall again in a 1996 book, "Green Was the Earth on the Seventh Day" (Random House) — turned him to the study of anthropology. He pursued his research in Peru, which made firmer his conviction that a group of tall, fair pre-Inca people, under the leadership of the legendary Kon-Tiki, sailed westward across to Polynesia. During World War II, Mr. Heyerdahl served in the Free Norwegian armed forces, mostly as a parachutist. After the war, he tried to interest publishers and scientists in his Polynesian theory, but came to realize that prevailing opinion was so strongly against it that a practical demonstration of its feasibility was the only answer.

He raised the money, overcame innumerable practical obstacles right down to the cutting of the long balsa logs he needed, recruited five friends to go with him and set off on the Kon-Tiki.

Mr. Heyerdahl's book "Kon-Tiki" was praised by Lewis Gannett in The New York Herald Tribune as "a superb adventure story." Harry Gilroy, in The New York Times, wrote: "Their saga, told by the expedition's organizer, is a revelation of how exciting science can become when it inspires a man with the heart of a Leif Ericsson and the merry story-telling gift of an Ernie Pyle."

The book was less successful with the scientific community. In 1958, for example, Dr. Alan S. C. Ross, a linguist at the University of Birmingham, England, said that language studies provided "an absolutely decisive disproof" of Mr. Heyerdahl's theory. There was Dr. Ross wrote, no relationship between Polynesian and any American language family.

Mr. Heyerdahl insisted, however, that in his mind he had proved his thesis — not that the crossing had been done, but that it could have been done. Next, Mr. Heyerdahl in 1953 led an archaeological expedition to the Galapagos Islands, 700 miles off the coast of Ecuador. He found evidence that convinced him that predecessors of the Inca had visited the islands, and that they had had the nautical sophistication to be able to return home against the wind.

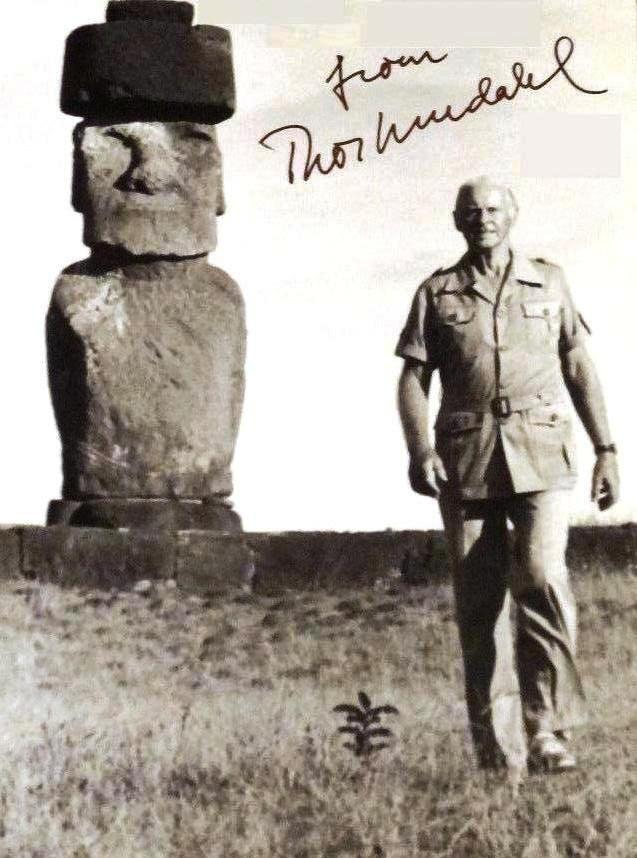

In 1955 and 1956, Mr. Heyerdahl tackled the mystery of remote Easter Island. He experimented with the techniques that might have been used in creating and placing upright the enormous stone figures for which the island is famous. "Aku-Aku," published in 1958, was a vivid account of the expedition. He later published scholarly accounts of this and the Kon-Tiki voyages.

Mr. Heyerdahl argued that Easter Island was also colonized by South Americans, which led one critic, the British archaeologist Paul G. Bahn, to write, "It is unfortunate that he has allowed his obsession with a South American connection to overshadow the far more interesting and important subjects of the islanders' cultural history, way of life and destruction of their environment."

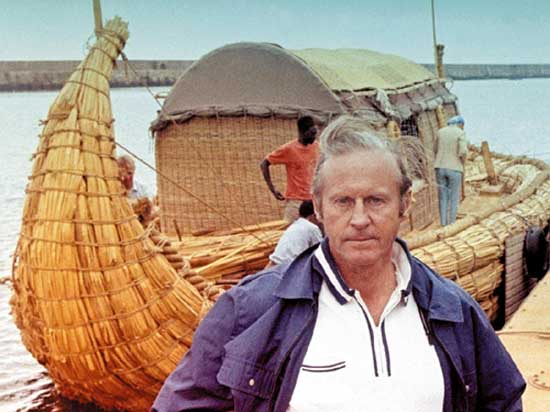

Mr. Heyerdahl then turned his attention to the possibility of a migration from Egypt to America, because of what he felt were striking cultural parallels, notably pyramid building. Most scholars doubted that the Egyptians had ships capable of so long a voyage. So Mr. Heyerdahl decided on a practical demonstration. Using ancient representations of Egyptian reed boats as his guide, he had a reed ship built and named it Ra, after the Egyptian sun god.

The first attempt, in 1969, fell short. The waterlogged ship had to be abandoned 600 miles from its destination in Barbados. Undaunted, Mr. Heyerdahl tried again the next year. It was on this successful 57-day journey, he said, that he first noted the "alarming" pollution of the ocean, a subject on which he continued to speak out forcefully.

Political strife shortened his 1977-78 voyage with another reed boat in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea. Reaching the coast of Ethiopia, he was refused permission to land because of warfare. He then abandoned the voyage, setting fire to the boat "to protest against the inhuman elements of the world of 1978." With these expeditions, Mr. Heyerdahl said, "I have proved that all the ancient pre-European civilizations could have intercommunicated across oceans with the primitive vessels they had at their disposal. I feel that the burden of proof now rests with those who claim the oceans were necessarily a factor in isolating civilizations. Most anthropologists think otherwise.

Mr. Heyerdahl's first wife, from whom he was divorced in 1949, died in 1969. He was also divorced from his second wife, Yvonne Dedekam-Simonsen Heyerdahl, who survives. In 1996, he married his present wife, Jacqueline Beer Heyerdahl, a French-born Hollywood actress.

Other survivors, besides the son Thor Jr. of Lillehammer, Norway, are another son, Bjorn, who lives in Italy; two daughters, Marian and Helene Elisabeth, both of Oslo; seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson