Moss Hart

Born October 24, 1904

New York City, New York, U.S.

Died December 20, 1961 (aged 57)

Palm Springs, California, U.S.

Spouse Kitty Carlisle

(m. 1946; his death 1961)

Children: Christopher and Catherine Hart

Moss Hart (October 24, 1904 – December 20, 1961) was an American playwright and theatre director.

Early years

Hart was born in New York City to Barnett Hart, a cigar maker, and Lillian Solomon. He had a younger brother, Bernard.

The family grew up in relative poverty with his English-born Jewish immigrant parents in the Bronx and in Sea Gate, Brooklyn.

Early on he had a strong relationship with his Aunt Kate, with whom he later lost contact due to a falling out between her and his parents, and Kate's weakening mental state. She piqued his interest in the theater and took him to see performances often. Hart even went so far as to create an "alternate ending" to her life in his book Act One. He writes that she died while he was working on out-of-town tryouts for The Beloved Bandit. Later, Kate became eccentric and then disturbed, vandalizing Hart's home, writing threatening letters, and setting fires backstage during rehearsals for Jubilee. But his relationship with her was formative. He learned that the theater made possible "the art of being somebody else… not a scrawny boy with bad teeth, a funny name… and a mother who was a distant drudge."

Career

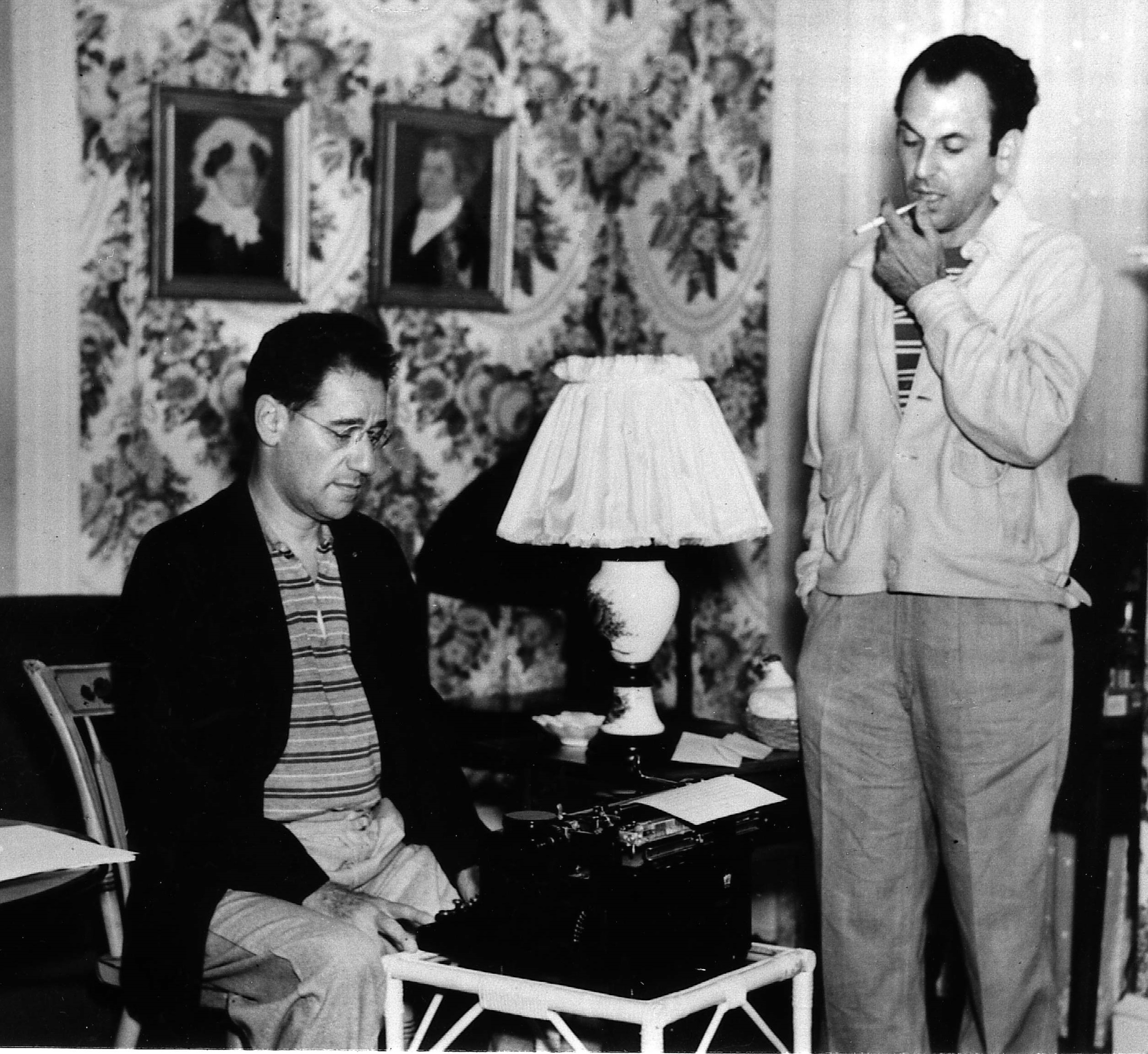

After working several years as a director of amateur theatrical groups and an entertainment director at summer resorts, he scored his first Broadway hit with Once in a Lifetime (1930), a farce about the arrival of the sound era in Hollywood. The play was written in collaboration with Broadway veteran George S. Kaufman, who regularly wrote with others, notably Marc Connelly and Edna Ferber. (Kaufman also performed in the play's original Broadway cast in the role of a frustrated playwright hired by Hollywood.) During the next decade, Kaufman and Hart teamed on a string of successes, including You Can't Take It with You (1936) and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939). Though Kaufman had hits with others, Hart is generally conceded to be his most important collaborator.

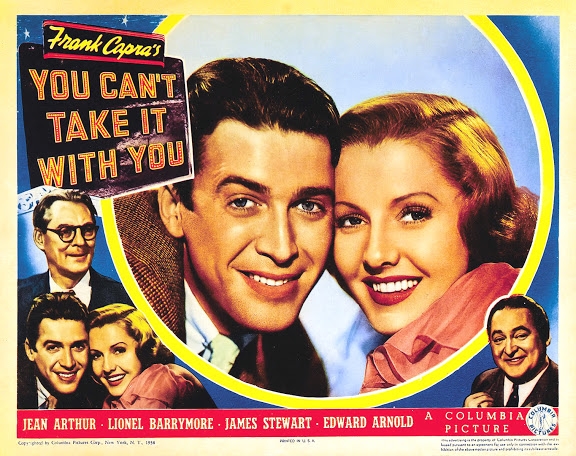

You Can't Take It With You, the story of an eccentric family and how they live during the Depression, won the 1937 Pulitzer Prize for drama. It is Hart's most-revived play. When director Frank Capra and writer Robert Riskin adapted it for the screen in 1938, the film won the Best Picture Oscar and Capra won for Best Director.

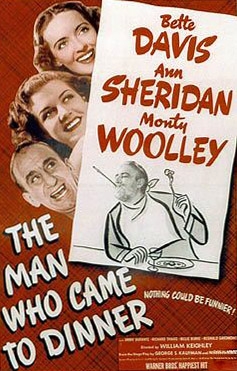

The Man Who Came To Dinner is about the caustic Sheridan Whiteside who, after injuring himself slipping on ice, must stay in a Midwestern family's house. The character was based on Kaufman and Hart's friend, critic Alexander Woollcott. Other characters in the play are based on Noël Coward, Harpo Marx, and Gertrude Lawrence.

After George Washington Slept Here (1940), Kaufman and Hart called it quits, although, throughout the 1930s, Hart worked both with and without Kaufman on several musicals and revues, including Face the Music (1932); As Thousands Cheer (1933), with songs by Irving Berlin; Jubilee (musical) (1935), with songs by Cole Porter; and I'd Rather Be Right (1937), with songs by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart. (Lorenz Hart and Moss Hart were not related.) Hart continued to write plays after parting with Kaufman, such as Christopher Blake (1946) and Light Up the Sky (1948), as well as the book for the musical Lady In The Dark (1941), with songs by Kurt Weill and Ira Gershwin. However, he became best known during this period as a director. Among the Broadway hits he staged were Junior Miss (1941), Dear Ruth (1944), and Anniversary Waltz (1954). By far his biggest hit was the musical My Fair Lady (1956), adapted from George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion, with book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. The show ran over seven years and won a Tony Award for Best Musical. Hart picked up the Tony for Best Director.

Hart was the host of an early television game show, Answer Yes or No, in 1950. Arlene Francis was one of the panelists.

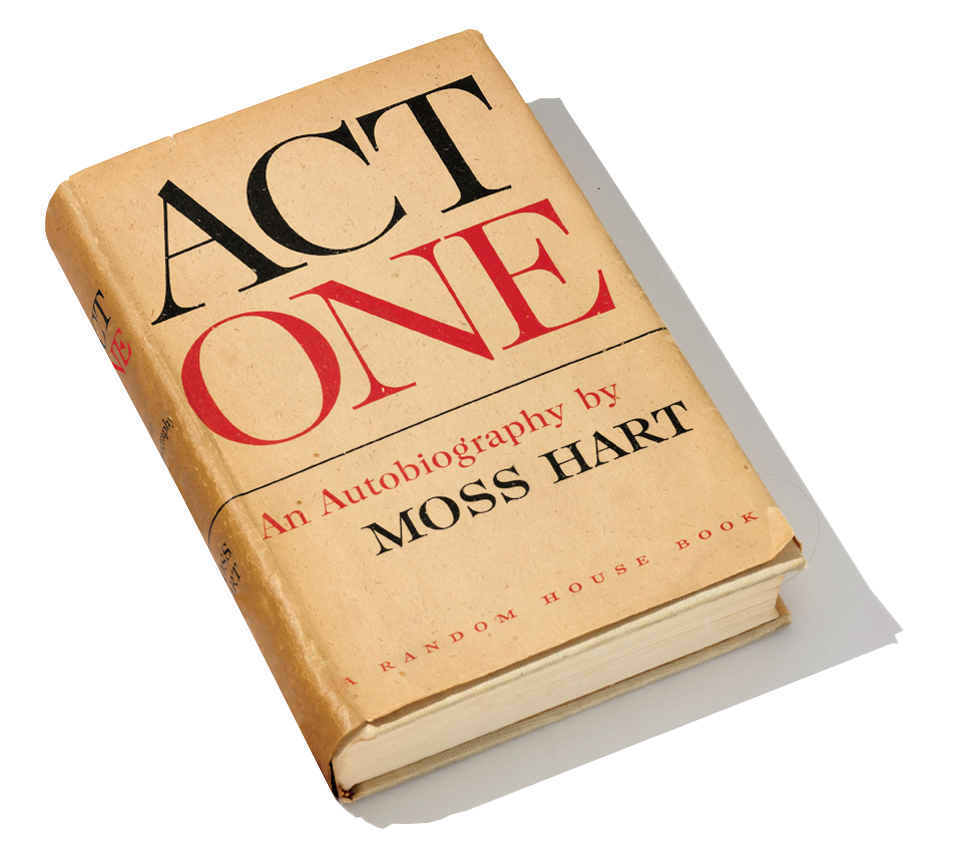

Hart also wrote some screenplays, including Gentleman's Agreement (1947) – for which he received an Oscar nomination – Hans Christian Andersen (1952) and A Star Is Born (1954). He wrote a memoir, Act One: An Autobiography by Moss Hart, which was released in 1959. It was adapted to film in 1963, with George Hamilton portraying Hart. The last show Hart directed was the Lerner and Loewe musical Camelot (1960). During a troubled out-of-town tryout, Hart had a heart attack. The show opened before he fully recovered, but he and Lerner reworked it after the opening. That, along with huge pre-sales and a cast performance on The Ed Sullivan Show, helped ensure the expensive production was a hit.

Personal life

Hart married Kitty Carlisle on August 10, 1946; they had two children. She was with him when he died. Still working as a TV game show panelist and touring lecturer in 2001 (at age 91), Carlisle did not comment publicly on a Hart biography by Steven Bach published that year, forty years after her husband's death.

Death

Moss Hart died of a heart attack at the age of 57 on December 20, 1961, at his winter home in Palm Springs, California.

He was entombed in a crypt at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.

Legacy

In 1972, 11 years after his death, Moss Hart was posthumously inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame. He was one of 23 people to be selected into the Hall of Fame's first-ever induction class that year. Alan Jay Lerner gave tribute to Hart in his memoir, The Street Where I Live.

Moss Hart Awards

The New England Theatre Conference offers the Moss Hart Memorial Award at their annual convention to theater groups in New England which put forth imaginative productions of exemplary scripts. These awards are designed to honor Moss Hart as well as the award recipients. The Moss Hart Award has been referred to as the New England Tony Award.

Work

Plays

1930 Once In A Lifetime (Kaufman and Hart)

1934 Merrily We Roll Along (Kaufman and Hart)

1936 You Can't Take It with You (won a Pulitzer Prize) (Kaufman and Hart)

1937 I'd Rather Be Right (Kaufman and Hart)

1939 The Man Who Came to Dinner (Kaufman and Hart)

1940 George Washington Slept Here (Kaufman and Hart)

1941 Lady in the Dark, with Kurt Weill and Ira Gershwin

1943 Winged Victory

1948 Light Up the Sky

Screenplays

1944 Winged Victory

1947 Gentleman's Agreement

1952 Hans Christian Andersen

1954 A Star Is Born

Autobiography

1959 (1989) Act One: An Autobiography. New York: St. Martin's Press. 1989 [1959].

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson  Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson  Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson