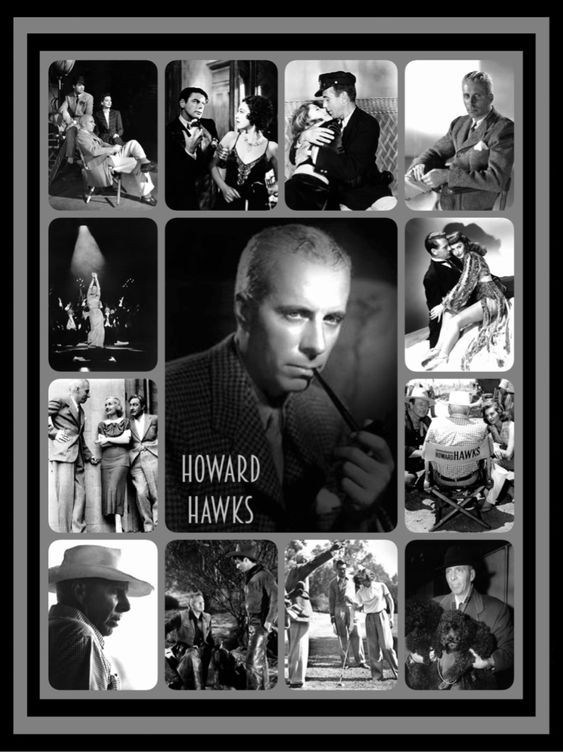

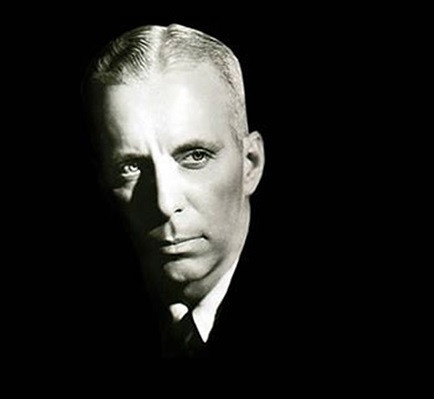

16 Must-See Howard Hawks Films (VIDEO)

“His Girl Friday,” 1940 (*****). One of the reasons Hawks liked working with Cary Grant was his extraordinary facility with dialogue. He could whip it out fast, add flourishes and make it sing. And in this remake of play-turned-movie “The Front Page,” recast with Rosalind Russell in the male role of ace reporter Hildy Johnson, Hawks pushed his actors to perform with an exhilarating adrenaline rush. We know that newspaper editor Walter Burns still loves his ex-wife Hildy for, among other things, being a consummate reporter. He manipulates the pin-striped scribe by hooking her onto a great story–which just happens to fall into her lap–and at the same time dive-bombing her relationship with her bumbling square-jawed fiancé, played by good-hearted sap Ralph Bellamy. It’s fun watching her dive into what she’s good at–we root for the two hardboiled news junkies to get back together.

“Red River,” 1948 (*****). If you don’t like “Red River,” you don’t like the movies. This was only sexy Monty Clift’s second role, and here he plays an orphaned young man who grows up under the wing of John Wayne’s gruff Thomas Dunson, a beleaguered cattle rancher with a broken heart and delusions of grandeur. But on the road to Red River, where Dunson hopes to have a better life, Matthew (Clift) turns against him, wanting a piece of the pie. The alleged off-screen romance between Clift and John Ireland, who duke it out over the size of their “revolvers,” imbues the film with a hard-to-ignore sexual tension — and for a John Wayne movie, it’s pretty steamy. Arthur Rosson codirected the film’s big set pieces, which involve a hell of a lot of cattle.

“To Have and Have Not,” 1944 (*****). The story goes that Hawks bet Ernest Hemingway he could make a good film from what he regarded to be the author’s worst novel. The two ended up collaborating on the story for the Bogart-Bacall classic, which actually bears little resemblance to the original source material. Set in 1940 Martinique under the Vichy Regime, Bogie plays a fishing boat captain who warily gets involved with the smuggling of French Resistance rebels. A knockout “Slim” woman (19-year-old Bacall) catches his eye, and the rest is history, both onscreen and off. While the chemistry between the two B’s is crackling, Hoagy Carmichael almost gets away with the show as the local bar’s crooning piano player (his “Hong Kong Blues” is particularly fabulous — watch below). –Beth Hanna

“Scarface,” 1932 (*****). Hawks’s first masterpiece arrived in theaters after “Little Caesar” and “The Public Enemy,” but no contemporaneous production crystallized the dark poetry of the gangster movie with such terrifying commitment as “Scarface.” Loosely based on the life of Al Capone, the film belies that notion that its director was anything but a master stylist, from the whistling shadow of Tony Camonte (Paul Muni) to a machine gun’s staccato reports turning the pages of the calendar. As the bodies pile up and Tony assumes the trappings of a robber baron, “Scarface” narrows the space between organized crime and big business to the vanishing point: money may illustrate power, but violence is capitalism’s currency. What distinguishes “Scarface” from other entries in the genre, however, is how precisely it renders a failed system’s human quotient, the near-impenetrable barriers of class. Tony, in a ghastly striped robe, played by Muni with pained fastidiousness, apes the style of princes but reveals himself ever the pauper. “Kinda gaudy, isn’t it?” his love interest, Poppy (Karen Morley), comments. “Ain’t it, though?” he says. “Glad you like it.” The billboard of the iconic final image, cruelly proclaiming “THE WORLD IS YOURS,” provides a bleak reminder that we’re all similarly desperate to buy the promise, even if we can’t afford the price.

“Bringing Up Baby,” 1938 (****1/2). How much mayhem can arise when you’ve got a leopard, an irascible dog and a dinosaur skeleton on the scene? This Hawks film is the quintessential and towering classic of screwball comedies — loopy heiress Katharine Hepburn can’t shake the idea she’s in love with zoologist Cary Grant (and who can blame her), and eventually — after much tracking down of a big cat named Baby and flailing around on the bones of a brontosaurus — he can’t shake the idea either. As an actor who Hawks liked to put in drag from time to time (see: “I Was a Male War Bride”), look out for Grant’s very funny scene in a fluffy nightgown.

“Ball of Fire,” 1941 (****1/2). Any screwball comedy that involves Barbara Stanwyck and a group of lexicographers is bound to entertain, and Hawks’ hilarious film about two very different worlds crashing into one another — with, well, fiery results — goes above and beyond the call of duty. Stanwyck is Sugarpuss O’Shea, a smart-mouthed nightclub singer on the lam from the mob. She shacks up with Professor Potts (Gary Cooper, in wonderful scholarly naif mode) and his wordsmith colleagues. The film nabbed four Oscar nominations, including a Best Actress nod for Stanwyck, as well as one for Billy Wilder and Thomas Monroe for Original Screenplay.

“The Big Sleep,” 1946 (****1/2). Screenwriters William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman passed this screenplay around like a hot potato before it finally landed in Hawks’ lap. It’s based on Raymond Chandler’s 1939 Philip Marlowe (here, Humphrey Bogart) novel. Marlowe is tasked by the Sternwoods to chase debts before Lauren Bacall’s Vivian Rutledge pulls back the curtain on a seedy murder mystery. Their chemistry, natch, smothers the screen as it did in “To Have and Have Not,” but “Big Sleep” is also fun to watch knowing that the Hays Code hacked this one to bits. But its hothouse of sexuality is still visible.

“Only Angels Have Wings,” 1939 (****). Written by frequent Hawks collaborator Jules Furthman, this aviator adventure is pure Hawks and followed up his flop “Bringing Up Baby.” It lays out many of his favorite themes: a group of men perform demanding and dangerous work at a high level. In this case Cary Grant leads a group of fliers equipped with rickety aircraft who must ferry mail and goods in and out of a treacherous canyon under variable weather conditions. They risk death every time they take off. Jean Arthur is the awkward fish out of water who wanders into this South American way station, tries to make sense of the situation and falls for aloof Grant, natch. He may still harbor feelings for his ex (Rita Hayworth), who also shows up, with her husband (Richard Barthelmess). Hawks wanted Arthur to play the role with more sensual allure–which Hayworth had in spades. But Arthur didn’t get it. After she saw Lauren Bacall in “To Have and Have Not” she told the director she should have done it his way.

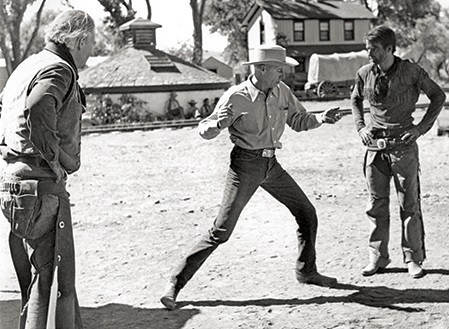

“Rio Bravo,” 1959 (****). This late great Hawks western rolls between ratcheting up tension and explosions of violence and quieter comic and romantic interludes. Hawks gives the mature John Wayne one of his more nuanced characters, opposite yet another of Hawks’ resourceful tough girls, exquisitely played by Angie Dickinson. She quietly softens up Wayne, forcing him to make human contact –a trope continued in several of his later films. Walter Brennan and singer Ricky Nelson make enjoyable sidekicks.

“Sergeant York,” 1941 (****). Gary Cooper naturally won the Best Actor Oscar for his performance in this B&W World War I biopic about sharpshooting, overtly emotional, deeply sincere Alvin York. Many writers were involved with the screenplay, including John Huston, but “Sergeant York” fluidly tracks York’s progression from Tennessee hick to all-out, religiously reborn pacifist to decorated war hero. The real-life York, initially leery of the film, insisted that Gary Cooper, and only Gary Cooper, could play him in the movie. And it paid off.

“I Was a Male War Bride,” 1949 (****). Hawks loved to rewrite the marriage plot (see the long-betrothed protagonists of “Monkey Business,” or the sharp-tongued exes of “His Girl Friday”), nowhere more explicitly than in his postwar comedy “I Was a Male War Bride.” The film places feisty American Lieutenant Catherine Gates (Ann Sheridan), not Captain Henri Rochard (Cary Grant, not even trying to sound French), quite literally in the driver’s seat: lacking the requisite motorcycling license, Rochard’s relegated to the sidecar on their journey through Central Europe. Hawks dispenses with the veneer of romantic suspense by having them marry at the halfway mark, in an astute series of dissolves between civil, military, and religious ceremonies. (“I don’t see how we could get a divorce,” Gates jokes. “It’d be something like unwinding the inside of a golf ball.”) The climax features Rochard searching for a place to sleep the night before sailing with Gates for America, turned away at every door because his status as a “male war bride” resists easy classification. It seems in retrospect a sly, keen commentary on the director’s chameleonic talents: Rochard is a man of many genres, much like Hawks himself.

“Twentieth Century,” 1934 (***1/2) This trapped-on-a-cross-country-train Hollywood romance, Hawks’ only previous farce before “Bring Up Baby,” pits the great John Barrymore–grandfather of Drew–in his prime against one of the great comediennes of the silver screen, Carole Lombard, who could handle herself with anyone. He’s a show business impresario trying to recapture his mojo via his former love, now a star. These two ship-smart antagonists cross wits and wiles and exchange satisfyingly sexy banter.

“Monkey Business,” 1952 (***1/2). The opening minutes of “Monkey Business” witness Edwina Fulton (Ginger Rogers) coaxing her absent-minded husband, chemist Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant), out of his brainstorm’s clouds. Against the mad world of joyrides, honeymoon suites, and mistaken identities that Hawks and company create in this antic comedy, the sequence is a delicate soft-shoe routine, and soon the Fultons are amorous enough to let the phone ring unanswered. Indeed, though Esther, a naughty chimpanzee in Fulton’s lab, adds her elixir of youth to a water cooler, it’s never clear the formula offers much more than a placebo effect. After a day cavorting with secretary Lois Laurel (Marilyn Monroe), Barnaby describes being young again as “maladjustment, idiocy, and a series of low-comedy disasters.” This also happens to be an apt synopsis of “Monkey Business,” for at the heart of Hawks’s comic genius was his deep understanding of the genre, and of how to use the unexpected, the self-reflexive, and the utterly insane to blow it up from the inside. “The history of discovery is the history of people who didn’t follow rules,” Barnaby tells his assistant, but the motto is Hawks’s through and through.

“The Thing From Another World,” 1951 (***1/2). Did Hawks direct “The Thing From Another World”? This question has gotten film experts, and the film’s cast members, all rankled for some time, as Christian Nyby ultimately got the credit for this sci-fi B-movie that inspired John Carpenter’s “The Thing.” A drive-in-style screening is perfect for this adaptation of a John W. Campbell story about the fight between the government and an elusive, rapidly growing alien species. Though the creatures, which look more like tawdry Frankenstein monsters, aren’t as frightening as Carpenter’s, Hawks’ (or whoever’s) direction, and Russell Harlan’s shadowy visuals crank up the PG-rated thrills.

“Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” 1953 (***). Marilyn Monroe perfected her could-be thankless stereotype in Howard Hawks’ glittering, deceptively whip-sharp “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” where Monroe plays the blonde, diamond-oggling yin to Jane Russell’s brunette, salty yang. Both actresses’ musical and comedic chops are on fine display here; for Monroe, look out for the sequence where she gets stuck attempting to pass her derriere through a ship’s porthole and must enlist a nine-year-old millionaire for help; meanwhile Russell owns her poolside routine basking in the glow of scantily clad male swimmers.

“Air Force,” 1943 (**1/2). Produced in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Hawks’s wartime drama is, for better and for worse, an unapologetic product of its time. Its fictional story of the Mary-Ann, a B-17 bomber that arrives in Hawaii in the midst of the Japanese attack — unarmed and out of fuel, no less — combines thinly veiled propaganda with a perceptive treatment of servicemen’s cramped camaraderie. As the Mary-Ann’s crew (featuring John Garfield, Gig Young, and Harry Carey, among others) continues on toward the Philippines, listening in over the radio as Roosevelt declares war, Hawks forges a surprisingly graceful portrait of patriotic cheer as but one part of the coming conflict. Hardship and death portend, too, and the nobility of sacrifice cannot assuage the accompanying grief. Even in this, the most hidebound of genres, Hawks — with the exception of the film’s over-the-top air battle climax — displays the clear-eyed, personal touch that made him the cinema’s most versatile master.

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson