Helen Keller, 87, Dies

Special to The New York Times

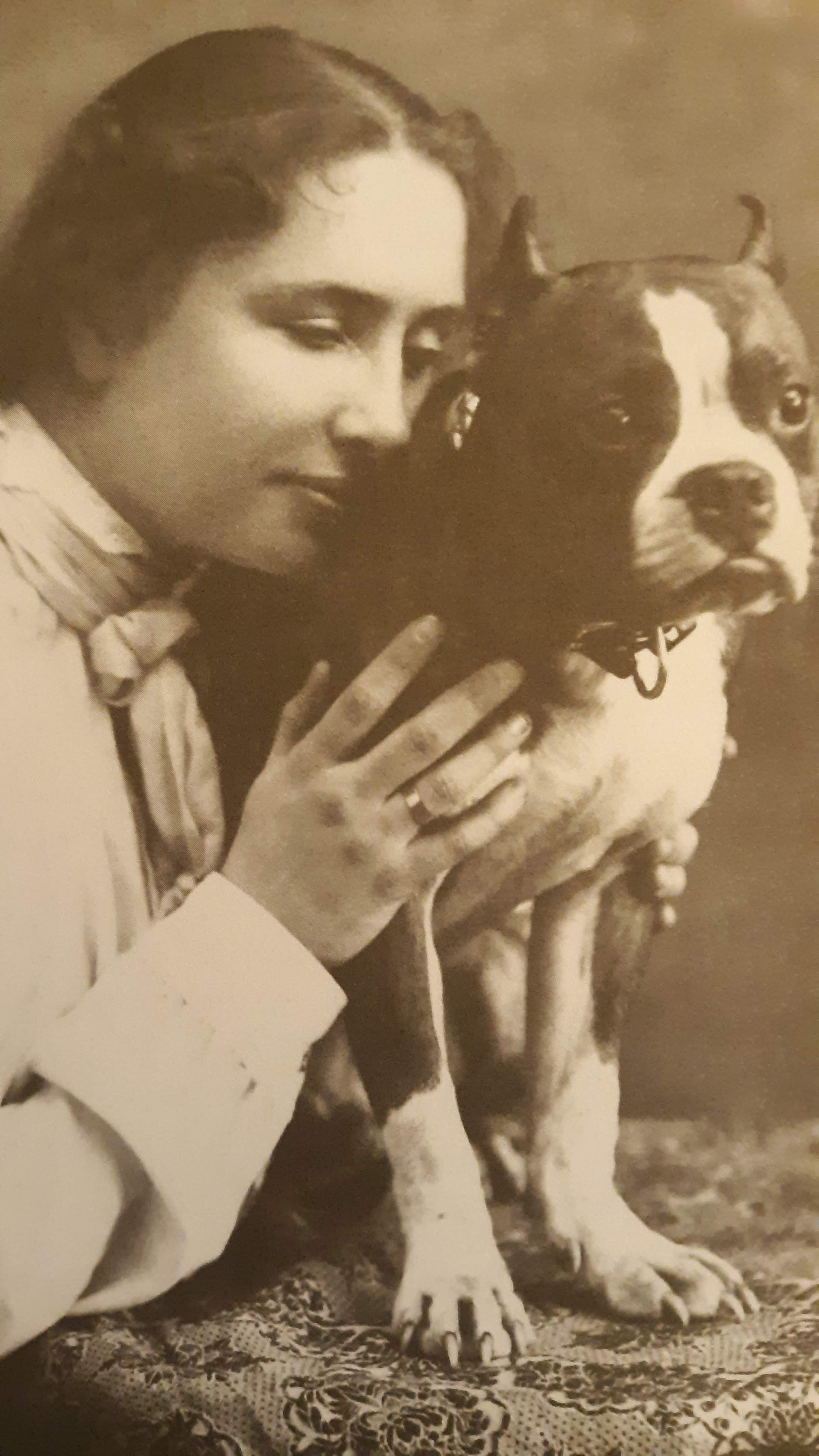

WESTPORT, Conn., June 1--Helen Keller, who overcame blindness and deafness to become a symbol of the indomitable human spirit, died this afternoon in her home here. She was 87 years old.

"She drifted off in her sleep," said Mrs. Winifred Corbally, Miss Keller's companion for the last 11 years, who was at her bedside. "She died gently." Death came at 3:35 P.M.

She is survived by a brother, Phillips B. Keller of Dallas, and a sister, Mrs. Mildred Tyson of Montgomery, Ala.

After private cremation, a funeral service will be held at the National Cathedral in Washington. No date has yet been set.

Triumph Out of Tragedy

By ALDEN WHITMAN

For the first 18 months of her life Helen Keller was a normal infant who cooed and cried, learned to recognize the voices of her father and mother and took joy in looking at their faces and at objects about her home. "Then" as she recalled later, "came the illness which closed my eyes and ears and plunged me into the unconsciousness of a newborn baby."

The illness, perhaps scarlet fever, vanished as quickly as it struck, but it erased not only the child's vision and hearing but also, as a result, her powers of articulate speech.

Her life thereafter, as a girl and as a woman, became a triumph over crushing adversity and shattering affliction. In time, Miss Keller learned to circumvent her blindness, deafness and muteness; she could "see" and "hear" with exceptional acuity; she even learned to talk passably and to dance in time to a fox trot or a waltz. Her remarkable mind unfolded, and she was in and of the world, a full and happy participant in life.

What set Miss Keller apart was that no similarly afflicted person before had done more than acquire the simplest skills.

But she was graduated from Radcliffe; she became an artful and subtle writer; she led a vigorous life; she developed into a crusading humanitarian who espoused Socialism; and she energized movements that revolutionized help for the blind and the deaf.

Teacher's Devotion

Her tremendous accomplishments and the force of assertive personality that underlay them were released through the devotion and skill of Anne Sullivan Macy, her teacher through whom in large degree she expressed herself. Mrs. Macy was succeeded, at her death in 1936, by Polly Thomson, who died in 1960. Since then Miss Keller's companion had been Mrs. Winifred Corbally.

Miss Keller's life was so long and so crowded with improbable feats--from riding horseback to learning Greek--and she was so serene yet so determined in her advocacy of beneficent causes that she became a great legend. She always seemed to be standing before the world as an example of unquenchable will.

Many who observed her--and to some she was a curiosity and a publicity-seeker--found it difficult to believe that a person so handicapped could acquire the profound knowledge and the sensitive perception and writing talent that she exhibited when she was mature. Yet no substantial proof was ever adduced that Miss Keller was anything less than she appeared--a person whose character impelled her to perform the seemingly impossible. With the years, the skepticism, once overt, dwindled as her stature as a heroic woman increased.

Miss Keller always insisted that there was nothing mysterious or miraculous about her achievements. All that she was and did, she said, could be explained directly and without reference to a "sixth sense." Her dark and silent world was held in her hand and shaped with her mind. Concededly, her sense of smell was exceedingly keen, and she could orient herself by the aroma from many objects. On the other hand, her sense of touch was less finely developed than in many other blind people.

Tall, handsome, gracious, poised, Miss Keller had a sparkling humor and a warm handclasp that won her friends easily. She exuded vitality and optimism. "My life has been happy because I have had wonderful friends and plenty of interesting work to do," she once remarked, adding:

"I seldom think about my limitations, and they never make me sad. Perhaps there is just a touch of yearning at times, but it is vague, like a breeze among flowers. The wind passes, and the flowers are content."

This equanimity was scarcely foreshadowed, in her early years. Helen Adams Keller was born on June 27, 1880, on a farm near Tuscumbia, Ala. Her father was Arthur Keller, an intermittently prosperous country gentleman who had served in the Confederate Army. Her mother was the former Kate Adams.

After Helen's illness, her infancy and early childhood were a succession of days of frustration, manifest by outbursts of anger and fractious behavior. "A wild, unruly child" who kicked, scratched and screamed was how she afterward described herself.

Her distracted parents were without hope until Mrs. Keller came across a passage in Charles Dickens's "American Notes" describing the training of the blind Laura Bridgman, who had been taught to be a sewing teacher by Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe of the Perkins Institution in Boston. Dr. Howe, husband of the author of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," was a pioneer teacher of the blind and the mute.

Examined by Bell

Shortly thereafter the Kellers heard of a Baltimore eye physician who was interested in the blind, and they took their daughter to him. He said that Helen could be educated and put her parents in touch with Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone and an authority on teaching speech to the deaf. After examining the child, Bell advised the Kellers to ask his son-in-law, Michael Anagnos, director of the Perkins Institution, about obtaining a teacher for Helen.

The teacher Mr. Anagnos selected was 20-year-old Anne Mansfield Sullivan, who was called Annie. Partly blind, Miss Sullivan had learned at Perkins how to communicate with the deaf and blind through a hand alphabet signaled by touch into the patient's palm.

"The most important day I remember in all my life is the one on which my teacher came to me," Miss Keller wrote later. "It was the third of March, 1887, three months before I was 7 years old.

"I stood on the porch, dumb, expectant. I guessed vaguely from my mother's signs and from the hurrying to and fro in the house that something unusual was about to happen, so I went to the door and waited on the steps."

Helen, her brown hair tumbled, her pinafore soiled, her black shoes tied with white string, jerked Miss Sullivan's bag away from her, rummaged in it for candy and, finding none, flew into a rage.

Of her savage pupil, Miss Sullivan wrote:

"She has a fine head, and it is set on her shoulders just right. Her face is hard to describe. It is intelligent, but it lacks mobility, or soul, or something. Her mouth is large and finely shaped. You can see at a glance that she is blind. One eye is larger than the other and protrudes noticeably. She rarely smiles."

It was days before Miss Sullivan, whom Miss Keller throughout her life called "Teacher," could calm the rages and fears of the child and begin to spell words into her hand. The problem was of associating words and objects or actions: What was a doll, what was water? Miss Sullivan's solution was a stroke of genius. Recounting it, Miss Keller wrote:

"We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Someone was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout.

"As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten--a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me.

"I knew then that 'w-a-t-e-r' meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free. There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that in time could be swept away."

Miss Sullivan had been told at Perkins that if she wished to teach Helen she must not spoil her. As a result, she was soon locked in physical combat with her pupil. This struggle was to thrill theater and film audiences later when it was portrayed in "The Miracle Worker" by Anne Bancroft as Annie Sullivan and Patty Duke as Helen.

The play was by William Gibson, who based it on "Anne Sullivan Macy: The Story Behind Helen Keller" by Nella Braddy, a friend of Miss Keller. Opening in New York in October, 1959, it ran 702 performances.

Miss Keller, then 36, fell in love with Peter Fagan, a 29-year-old Socialist and newspaperman who was her temporary secretary. The couple took out a marriage license, intending a secret wedding. But a Boston reporter found out about the license, and his witless article on the romance horrified the stern Mrs. Keller, who ordered Mr. Fagan out of the house and broke up the love affair.

"The love which had come, unseen and unexpected, departed with tempest on his wings," Miss Keller wrote in sadness, adding that the love remained with her as "a little island of joy surrounded by dark waters."

For years her spinsterhood was a chief disappointment. "If I could see," she said bitterly, "I would marry first of all."

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Mary Neeley

Mary Neeley

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Mary Neeley

Mary Neeley

Mary Neeley

Mary Neeley  Daniel Pinna

Daniel Pinna

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson  Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson