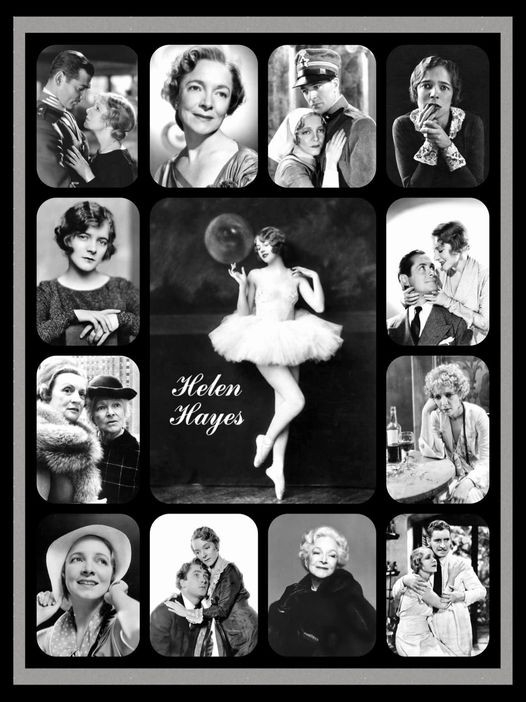

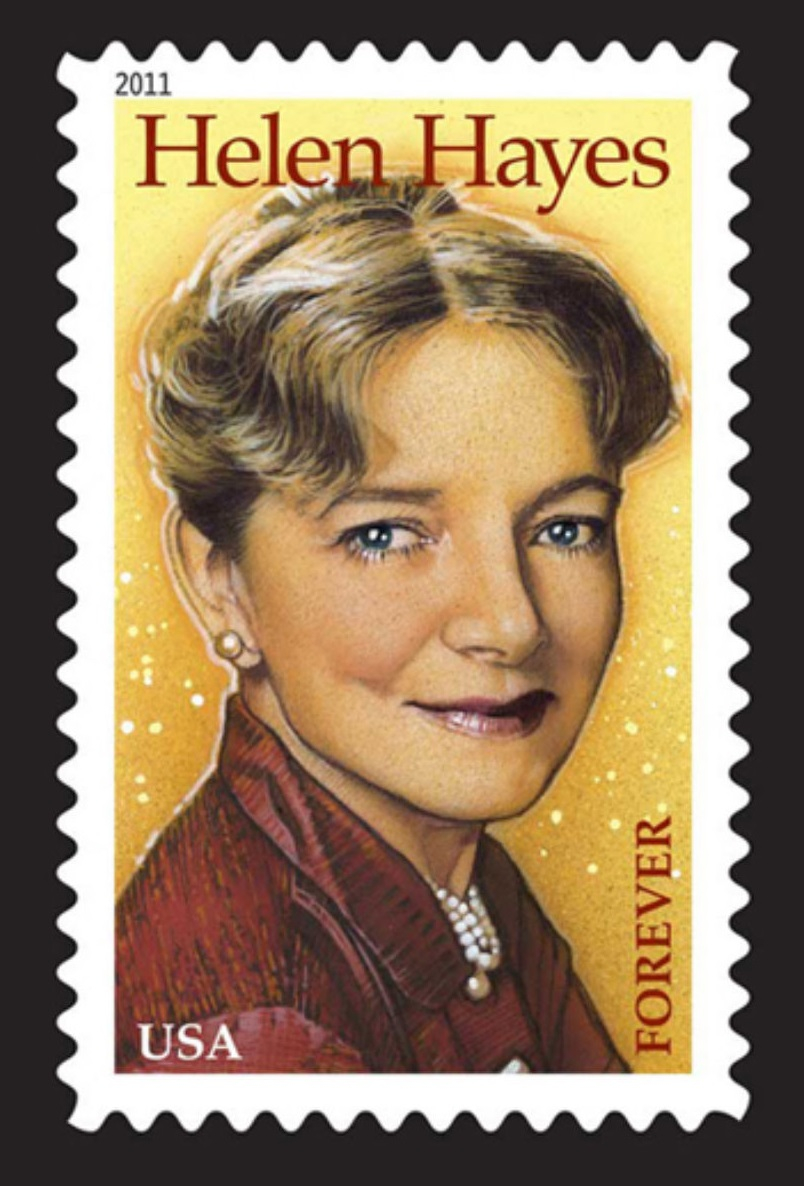

Helen Hayes, the diminutive and demure grande dame of the American theater, whose 87 years of stage, film, and television performances—as tots, ingenues, queens, nuns, and matriarchs—earned her the enduring affection of four generations, died Wednesday. She was 92.

She had been brought to Nyack Hospital in that New York City suburb and admitted on March 8th for treatment of congestive heart failure. Her family was with her when she died, a hospital spokeswoman said.

Miss Hayes' twin careers entranced her public. Her acting brought her two Academy Awards and Broadway's highest acclaim—a theater named for her. And then there was her exemplary personal life, as wife, mother, Catholic, and a dedicated volunteer for medical research and the elderly, a civic campaign she embarked on after her only daughter, Mary, died of polio at age 19.

Perhaps the last of America's great ladies of the stage, the Washington-born actress, who stood 5-feet-nothing and once described herself to a magazine as "a little Irish biddy," also managed, without tiger skins or tantrums, to outlast and usually out-act Hollywood's ferociously slinky glamour queens on their own film turf.

Offstage, Miss Hayes' life was every bit as ladylike—although not always such smooth sailing—as her conduct in front of audiences. It was an appeal she was at a loss to explain, except, she wrote once, "I sometimes think that I am the triumph of the familiar over the exotic."

And it may have been that familiarity that enabled her to become one of the very few actors or actresses to cross comfortably between film and stage, although she always preferred the latter.

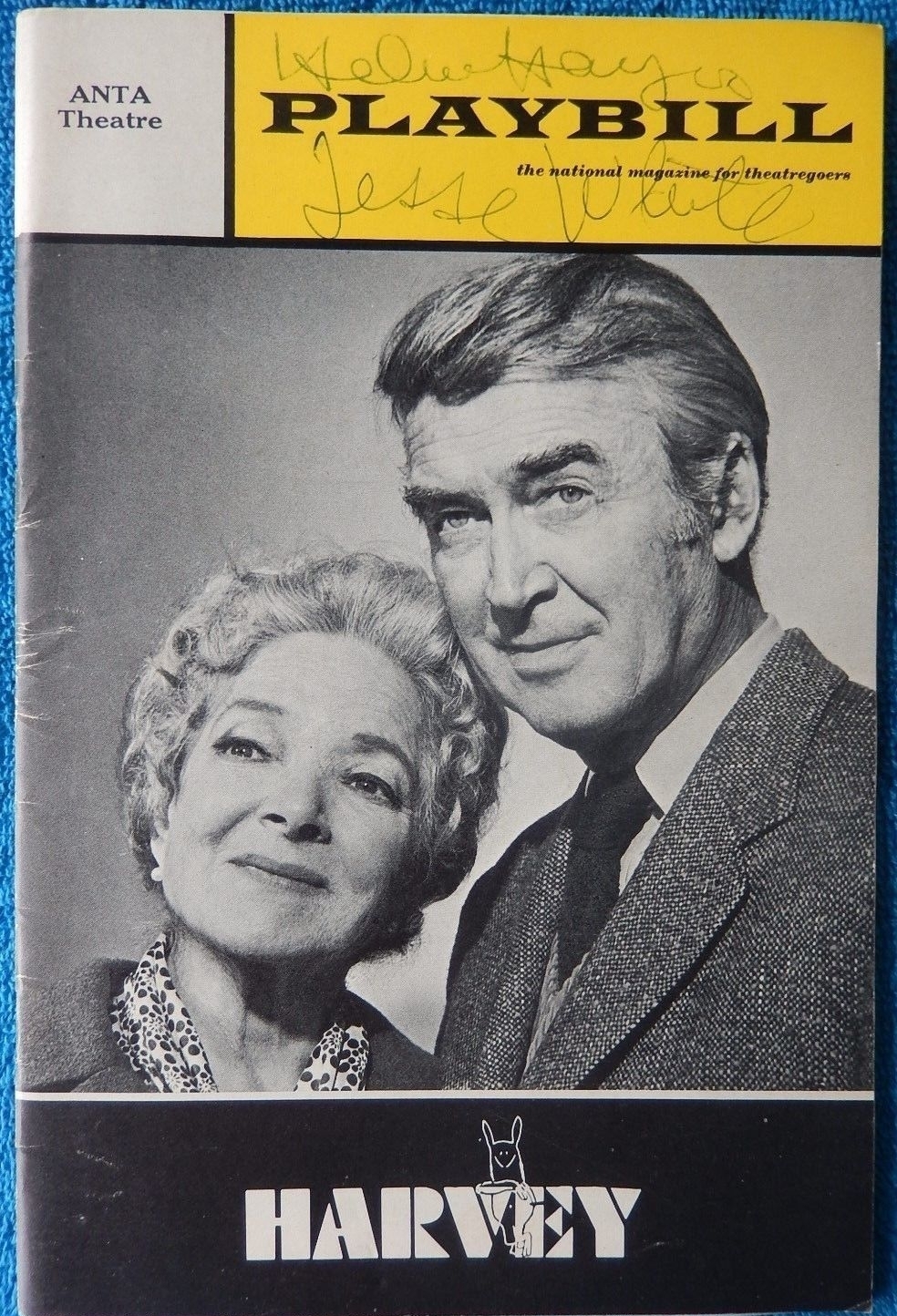

With her disciplined stage technique and personal uprightness (she once lost an alphabet game among New York's 1920s literati because she did not know swear words), she was never entirely at ease in Hollywood, whose star system and "arrogance" she came to loathe, especially after the less-than-kind treatment accorded her husband, writer and playwright Charles MacArthur. She nonetheless made more than a score of movies and beat Hollywood at its own game, winning Oscars almost 40 years apart: as best actress in her first major film role, "The Sin of Madelon Claudet," in 1932, and as best supporting actress in "Airport" in 1970. They ranged from Margaret in "Dear Brutus" by Sir James M. Barrie and Amanda in Tennessee Williams' "The Glass Menagerie," to playing Harriet Beecher Stowe, Cleopatra in George Bernard Shaw's "Caesar and Cleopatra," Volumnia in Shakespeare's "Coriolanus" and Mrs. Antrobus in "The Skin of Our Teeth." With her daughter, Mary, she performed in "Alice-Sit-by-the-Fire" and "Good Housekeeping"—during which Mary caught the cold that turned out to be polio.One of her most memorable stage roles was "Victoria Regina" (a part she acted 969 times, and of which, years later, seeing tapes of her national tour, she remarked scornfully, "Phony, totally overdone . . . all those Shrine auditoriums where you worked so hard to reach the balcony"). The other was as another queen, the doomed "Mary of Scotland," a role Miss Hayes believed tested her true talent—whether a sprightly 5-foot Irishwoman could convincingly portray the tall, romantic, tragic Scots queen. "I became" she said, "the tallest 5-foot woman in the world."

She turned zealously to movies and television, bringing to them all (a "Love Boat" episode with her son, actor James MacArthur, a documentary on aging, "The Snoop Sisters" with Mildred Natwick, even a Walt Disney trifle like "Herbie Rides Again") the stage dignity even those minor roles could not impede.

Miss Hayes also never stopped learning her craft or being critical of herself. She studied voice and took acting classes of varying value (in one, students imitated seals sunning on the ice, and a fat woman rolled over on her). Even her aging, fat French poodle taught Miss Hayes something. As she watched him loll on the floor and lap up his owners' kind words, Miss Hayes decided that was exactly how her Queen Victoria should respond to Prime Minister Disraeli's high-flown flattery.

Radio Performance"I had learned to be an actress," Miss Hayes wrote. "I never learned to be a star."

She did give it a half-hearted try. Her friend, actress Lynne Fontanne, scolded her for not being glamorous and doggedly dyed Miss Hayes' hair blond. "My indifference to style has driven friends crazy," she confessed in one of her autobiographies. "It earned me the reputation at 24 of being dowdy."

She became the great and good lady, as the imperious Russian dowager empress, Ingrid Bergman's aunt in "Anastasia," a role she took as therapy within months of her husband's death in 1956. She added bits of mischief in the comic fantasy "Mrs. McThing," and years later polished her conniving, fuddled old-lady act as a stowaway in "Airport," a role that earned her the second Oscar. Whit Bissell, Jacqueline Bisset and Helen Hayes in "Airport." (Universal Pictures)

In 1928, Hayes and her husband bought their 21-room, white Victorian house in Nyack overlooking the Hudson River.

Successive birthdays brought old friends and new honors to the house, where she lived for more than 60 years—honors like the "Helen Hayes Rose," a yellow blossom with a touch of pink, now planted in the garden at the Actors' Fund Home in Englewood, N.J., another of her charities. The first Helen Hayes Theater was razed, but another was named for her. Theater, she admitted in 1987, is "a little sickly in New York." Even reminders of age delighted her. When grandson Charles saw her 1933 film "The White Sister," he told classmate John Gable, "I saw your father kissing my grandma the other night."

Educated in Catholic schools partly because her mother was terrified of the vaccinations required by public schools, Miss Hayes shared her mother's religion and her devouring interest in theater—her mother's means of escaping a humdrum life. Miss Hayes' "only rebellion and a most unlikely change of script" was her marriage to the wayward, hard-drinking, quicksilver, witty, divorced journalist-playwright MacArthur, who with Ben Hecht co-authored "The Front Page."

It was a marriage of opposites that the acidulous critic Alexander Woollcott likened to "hang(ing) some chintz curtains on the lip of Vesuvius and call(ing) it home."

The 28-year-marriage that ended with MacArthur's death was a warp and woof of contradictions that made the fabric of their lives together so strong. "He saw the woman lurking in the girl," she wrote. "It was Charlie who gave my life reality, who handed me my sovereignty, the identity that completed my education as an actress and began it as a woman." It was a marriage "crammed with abysmal moments and glorious hours."

On MacArthur's arm, she entered the glittering orbit of his friends, the wits of New York, among whom even asking for the correct time demanded a cutting bon mot in reply.

After howls of protests that good-time Charlie was being stolen away by a shy little actress, they came to like her—if only because they needed someone who listened.

The story of their first meeting has become a poignant piece of Americana.

Party Incident. It was at a party and Irving Berlin was playing the piano with one finger. "The most beautiful young man" Miss Hayes said she had ever seen, walked up and asked, "Do you want a peanut?" As MacArthur poured them into her trembling hands, he added, "I wish they were emeralds."

(Over the years that line dogged them everywhere—including a 10th-anniversary dinner where a bowl of green-tinted peanuts was set at their table. It all so depressed MacArthur that, returning from World War II, he dumped a bag of emeralds in her lap and announced: "I wish they were peanuts.")

At another party, determined to impress her husband's clever friends, she took a deep breath and declared, "Anyone who wants my piano is willing to it," and after a profound pause, playwright George S. Kaufman, who had co-authored "To the Ladies" for Miss Hayes, said, "That's very seldom of you, Helen."

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson