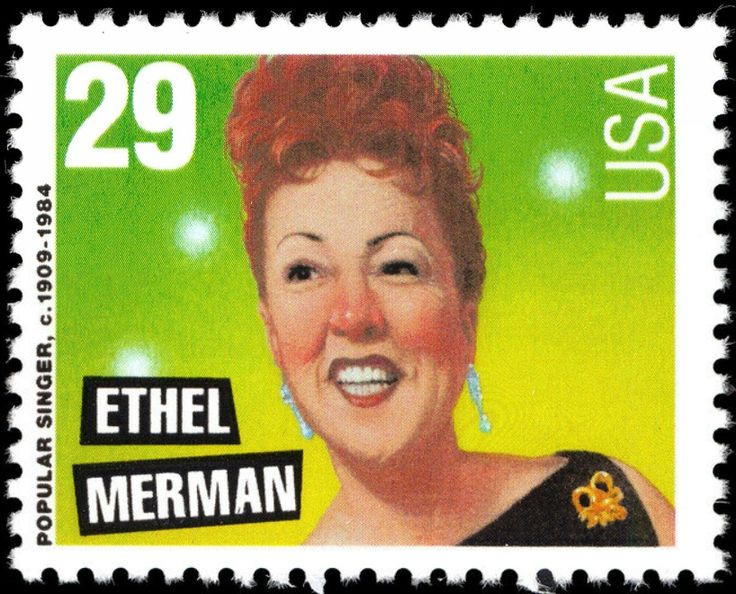

Ethel Merman, the musical-comedy star whose belting voice and brassy style entertained Broadway and movie audiences for 50 years, was found dead in her Manhattan apartment yesterday.

Miss Merman, who was 76 years old, had undergone surgery to remove a brain tumor last April. The Medical Examiner's office reported yesterday that she died of natural causes.

The singer's booming voice was first heard on a Broadway stage in 1930 when she brought down the house singing ''I Got Rhythm'' in the Gershwin musical ''Girl Crazy.'' Her last major appearance in New York was in 1982, when she took part in a Carnegie Hall benefit concert.

Miss Merman's most memorable shows included Cole Porter's ''Anything Goes'' and ''Dubarry Was a Lady,'' Irving Berlin's ''Annie Get Your Gun'' and the Jule Styne-Stephen Sondheim musical ''Gypsy,'' which she considered her best. Her 14 movies included ''Alexander's Ragtime Band,'' ''There's No Business Like Show Business'' and ''It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.''

Beginning in 1930, and for more than a quarter of a century thereafter, no Broadway season seemed really complete unless it had a musical with Ethel Merman. In that period, the chunky, aggressive star with the clarion voice, brash personality, shrewd comic sense and steel nerves was the darling of such master songwriters as George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and Jule Styne.

When her Broadway career all but ended in 1959 with what many of her admirers considered her finest performance, as the mother of the stripper in ''Gypsy,'' she had done 13 musicals, nearly all of them hits.

She returned for a brief run, in 1966, of an ''Annie Get Your Gun'' revival, and although the critics cheered her still-powerful voice, they questioned the wisdom of a 59-year-old playing a lovestruck girl. In 1970, she was the last of the six stars who played the title role in Jerry Herman's ''Hello, Dolly!'' In 1964, she had turned down the role and it went to Carol Channing.

Miss Merman made 14 movies, some of them based on her Broadway triumphs, had her own radio show and scored a huge national success in 1953 in a television special teamed with Mary Martin, perhaps the only Broadway musical star of her stature at the time.

But it was on Broadway that Miss Merman belonged. Composers vied for her, knowing she would hit every note on the mark, hold it as long as needed, give it the right shading, follow the trickiest rhythm flawlessly. Lyrics writers were equally certain that she would make every syllable distinct and evoke every bit of laughter from a comic line. Instant Nostalgia

Her delighted customers knew that when the ''belter'' strode onstage, turned her round eyes on them, raised her quizzical eyebrows and opened her wide mouth, they would get full value wherever they sat. She needed no hidden microphones. Equally important, they knew that when they bought tickets for a Merman show - usually well in advance - she would be there, her face beaming, strong arms churning, regardless of snowfall or flu epidemic. Her health was as legendary as her toughness and outspokenness.

In any gathering of showgoers, merely to mention a Merman show was enough to touch off a wave of nostalgia in which people began recalling - perhaps even singing - her hits. They included Gershwin's ''I Got Rhythm,'' from ''Girl Crazy''; ''Eadie Was a Lady,'' from ''Take a Chance''; ''Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries'' by Lew Brown and Ray Henderson, from the 1931 ''George White's Scandals''; ''Blow, Gabriel, Blow,'' ''I Get a Kick Out of You'' and ''You're the Top,'' from Porter's ''Anything Goes''; ''Ridin' High,'' from Porter's ''Red, Hot and Blue''; ''Friendship,'' from Porter's ''DuBarry Was a lady''; ''Let's Be Buddies,'' from Porter's ''Panama Hattie''; ''Doin' What Comes Natur'lly,'' ''You Can't Get a Man With a Gun,'' ''They Say It's Wonderful'' and ''I Got the Sun in the Morning,'' from Berlin's ''Annie Get Your Gun''; ''The Hostess With the Mostes' on the Ball'' and ''You're Just in Love,'' from Berlin's ''Call Me Madam,'' and ''Rose's Turn,'' from the Styne-Sondheim score for ''Gypsy.''

Her films included ''We're Not Dressing,'' ''Kid Millions,'' ''Strike Me Pink,'' ''Alexander's Ragtime Band,'' ''There's No Business Like Show Business'' and the Hollywood versions of ''Anything Goes'' and ''Call Me Madam.''

A self-taught singer, Miss Merman did not try to analyze her technique or style. When asked to explain her success, she said:

''I just stand up and holler and hope my voice holds out.'' Or: ''I leave the songs the way they came out of the composer's head.'' Or: ''Even if I don't know how I get the effects I end up with, I do have sense enough to know that I do all right. I'd be a dope if I didn't know that. I'd be even dopier if I changed the way I do it.''

''She's the best,'' Irving Berlin once said of her. ''You give her a bad song, and she'll make it sound good. Give her a good song, and she'll make it sound great. And you'd better write her a good lyric. The guy in the last row of the second balcony is going to hear every syllable.'' Turned Down Berlin's Revisions

Offstage, as well as in the theater, Miss Merman was a sort of symbol of the Broadway of her era, with her New York speech, gaudy jewelry, flamboyant, gum-chewing manner. Supremely self-confident, immune to opening- night jitters, she was in awe of no one in show business.

For example, there was the time when ''Call Me Madam'' was approaching its Broadway opening. Miss Merman, as usual, had let it be known even before rehearsals began that she would allow no changes in her songs less than a week before opening. A few days before the opening, however, Mr. Berlin rushed up to her with changes in lyrics for ''The Hostess With the Mostes' on the Ball.'' Miss Merman bluntly turned down the multimillionaire songwriter, saying:

''Call me Miss Bird's Eye. It's frozen.''

Once, when asked about her reputation for ruthlessness, she replied: ''I believe in asserting myself, but only for things that are important. Anybody who's worth her salt has to fight for her rights once in a while or get shoved around.''

Miss Merman worked hard during rehearsals and did not lower her standards during a long run. She demanded - and got - as much as 10 percent of the gross. 'Gypsy' Role Was Her Favorite

''When I do a show,'' she said, ''not to pat myself on the back, but when I do a show, the whole show revolves around me. And if I don't show up, they can just forget it.''

Sometimes Miss Merman exercised considerable control over a show before it went into production. This was the case with ''Gypsy.'' Jerome Robbins, the director, wanted Mr. Sondheim to write the music. Miss Merman felt he was too inexperienced, and insisted on Mr. Styne, who got the assignment. However, she agreed to let Mr. Sondheim do the lyrics.

Her role as Mama Rose in ''Gypsy'' was her favorite, she said years later, even though the character was largely unsympathetic. The Styne-Sondheim score climaxes with ''Mama's Turn,'' a complex, dramatic soliloquy that Miss Merman considered her most demanding moment in the theater, and some critics thought was her finest.

''It was like an opera to sing,'' she said. ''It went on for about 11 minutes, with tears, bumps and grinds, you name it.''

This hit led to what was probably the biggest disappointment of her career. After ''Gypsy'' opened, Mervyn LeRoy, the Hollywood producer-director, who was to do the film, saw the show many times and Miss Merman spent a good deal of time with him. She was convinced that Mr. LeRoy had promised her the Broadway role in the movie. When she learned that the part was to be given to Rosalind Russell, she was furious. She got Mr. Styne on the phone, and according to the book ''Sondheim & Co.,'' by Craig Zadan, demanded, in abusive and profane language, that he get her the movie part. Miss Russell won out. Tale Began in 1930

The pattern for Miss Merman's phenomenal success on Broadway began with her first show, a performance that became part of Broadway's colorful folklore.

In 1930, Miss Merman, barely 21, with a few years of nightclub singing, was onstage at the Brooklyn Paramount. Word drifted across the river about the big voice that was filling the Brooklyn movie theater during the stage show. Vinton Freedley, who was producing the new Gershwin show ''Girl Crazy,'' went to Brooklyn, heard her and persuaded George Gershwin to audition her. The composer liked her and hired her for the show, in which Willie Howard and Ginger Rogers got top billing.

On opening night, toward the end of the first act, the newcomer to Broadway swung into ''I Got Rhythm,'' rousing the savvy first-night audience with her power, rhythm and poise. She stopped the show. As the curtain came down, Mr. Gershwin rushed backstage and pleaded with her: ''Don't ever let anyone give you a singing lesson. It'll ruin you.'' No one ever did. 'It Was Exciting'

Some years later, Miss Merman, by now an established star, recalled that night, saying:

''In the second chorus of 'I Got Rhythm,' I held a high C note for 16 bars while the orchestra played the melodic line - a big, tooty thing - against the note. By the time I'd held that note for four bars the audience was applauding. They applauded through the whole chorus and I did several encores. It seemed to do something to them. Not because it was sweet or beautiful, but because it was exciting. Few people have the ability to project a big note and hold it. It's not just a matter of breath; it's a matter of power in the diaphragm. I'd never trained my diaphragm, but I must have a strong one. When I finished that song, a star had been born. Me.''

The star, whose real name was Ethel Agnes Zimmerman, was born of German and Scottish parents on Jan. 16, 1908, or 1909, or 1912 - the year changed as she grew older - in the Astoria section of Queens. As a child, she began traipsing with her father to political clubs and lodges, where she sang such songs as ''K-K-K-Katy,'' ''Maggie Dooley'' and ''How You Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm.'' Even then her voice was big and her pitch true.

Though she took a commercial course at high school and got a job as a stenographer, Miss Merman never doubted that she would become a singer. Thus, she left one job for another because she had heard that her boss at the second job knew important men in show business.

Once her boss gave her a letter to a Broadway producer who offered her a job in the chorus. She turned it down. She was determined to be a singer. When she went to the Palace with friends to watch the top performers in vaudeville, she would often imitate the singers and sometimes say she could sing better than the high-priced talent she had seen. 4 Marriages, 4 Divorces

While working as a secretary, Miss Merman got a singing job at a small nightclub. An agent, Lou Irwin, got her a six-month contract to sing for Warner Brothers, but in fairly typical Hollywood fashion, the movie studio did not use her as a singer. She offered to waive her salary if the studio would let her sing elsewhere during her contract. The studio agreed, and Miss Merman took nightclub jobs.

Thus, for $85 a week, less than half what she could have received from Warner Brothers for doing nothing, she was singing at a New York nightclub run by Clayton, Jackson and Durante - the last named was Jimmy Durante. There she met a pianist named Al Siegel, and the two got bookings at Long Island night spots. And then she got the offer to sing at the Brooklyn Paramount. Later, she was headlined at the New York Paramount and the Palace.

Miss Merman's personal life was much rockier than her professional career. Her four marriages all ended in divorce. The first, to William B. Smith, was brief. She then married Robert D. Levitt, a Hearst executive by whom she had two children, Ethel and Robert. The daughter committed suicide in 1967. Her third marriage was to Robert Six, then president of Continental Air Lines. The fourth was to Ernest Borgnine, the actor.

Though Miss Merman was successful in every kind of show business she tried, she never lost her partiality for Broadway.

''You may have done all right elsewhere,'' she said, ''but you haven't really done it until you face a New York first-night crowd.''

And, she said just over a year ago, ''Broadway has been very good to me - but then I've been very good to Broadway.''

The Medical Examiner's office said Miss Merman's body would be cremated, and a spokesman for the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home said that no information about the singer's death or possible memorial services would be released because of the wishes of her son, Robert Levitt.One night, while performing the song "Can You Use Any Money Today", a drunken audience member kept calling out to Merman while she performed, annoying both the audience and Merman herself. Finally, Merman got to the last line of the song, hit the first three notes, and then stopped the song. She then walked off the stage, through the wings, down the stairs and into the audience. She got to the drunken man, yanked him out of his seat, dragged him up the center aisle and through the doors that led out of the theater and literally threw the man out into the street. She then walked back into the theater, down the center aisle, up the stairs, through the wings onto the stage, got to dead center and hit the final note of the song as if nothing had happened.

Her favorite role was Mama Rose in "Gypsy", the last Broadway role she originated.

On April 7, 1983, Merman collapsed in her in Manhattan apartment while preparing to leave for Los Angeles to appear on the 55th Academy Awards. She was taken to Roosevelt Hospital, where, after undergoing exploratory surgery on April 11, the actress was diagnosed with stage 4 glioblastoma. It was reported that she underwent brain surgery to have the tumor removed, but in fact, it was inoperable and her condition was deemed terminal. Her health eventually stabilized enough for her to be brought back to her apartment in Manhattan. However, on February 15, 1984, Merman died of natural causes, 10 months after she was diagnosed with brain cancer.

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson