Marie Robards: Deadly Daughter

Dorothy Marie Robards — Marie to those who knew her — wasn’t the kind of kid anyone would expect to get into trouble. Smart, studious, and quiet, she learned to write in cursive by the first grade. In high school, she made good grades, played the clarinet, and took art and dance classes. She also enjoyed a close relationship with her mother, Beth Burroughs, and step-father, Frank Burroughs, who had been married since Marie was four years old. Marie even called him “dad.”

Her biological father, Steven Robards, she only saw once or twice a month. Steven and Beth had gotten married young and divorced after only a few years.

But in the summer of 1992, things would take a dramatic turn for the worse. The weekend before her 16th birthday, she came home to find Frank with another woman. Marie was furious.

However, when Marie told her mother what she’d caught Frank doing, Beth blamed herself rather than Frank. She worked long hours at an emergency room, she explained, and that probably had made Frank feel “neglected.” Marie could not understand why Beth would choose to stay with a man who had cheated on her. Consequently, she became sullen, especially towards Frank. She refused to listen to him and talked back to him. Finally, she told her mother she couldn’t stand living under the same roof as him.

Beth stuck by her decision to stay with Frank and “work on” their marriage. She made arrangements for Marie to go live with her parents in Fort Worth, Texas, about 45 minutes away. Five days later, Marie arrived back at the Burroughs’ home, begging to move back in.

But Frank had instituted a strict rule against that. In order to stop the children in their blended family from moving from parent to parent whenever they didn’t get their way, the rule was that once they moved out, they could never move back in.

So the decision was made for Marie to go live with her father back in Fort Worth. Steven, for his part, was excited to have his daughter come live with him. He often took her out to restaurants and movies. He immediately applied for a two-bedroom apartment in his complex; in the meantime, Marie slept on a rollaway bed in the dining room.

Marie, however, was not as happy with the arrangements. She was on the phone with her mother every night, long distance (this was back in the days when long-distance calls cost considerably more than local ones). She complained that he never cleaned the apartment and didn’t even have enough utensils in the kitchen. She hated her new high school, which was much bigger than her old one. At one point, she wrote her mother a letter threatening suicide. Beth just thought it was a typical teenager’s over-dramatic ploy to get her way.

After a few months went by, Marie seemed to settle into her new life. She was making excellent grades at her new school — especially in chemistry.

Then, on Feb. 17, 1993, Steven fell gravely ill. The two had shared a dinner of take-out Mexican food, then Steven had gone to an evening church service. He came home early complaining of stomach cramps. They kept getting worse, so at one point, Marie went to the apartment of Steven’s girlfriend, Sandra Hudgins, and told her that Steven was really sick. She stayed in Sandra’s apartment with her young son while Sandra went to check on Steven.

Sandra said that when she got there, Steven’s arms and legs were stiff, and he was having a hard time swallowing. He was foaming at the mouth. Sandra dialed 911 immediately.

When paramedics arrived, they tried to intubate Steven, but his throat was closed shut. At that point, Marie came back to the apartment. Sandra said Marie just stood in the doorway, frozen, likely in shock. As it became clear that Steven was dying, Sandra hugged her, turning the teenager’s face away so she wouldn’t see the awful sight. The coroner would later determine Steven’s cause of death was a heart attack. Later that night, Beth and Frank arrived to take Marie back to their house.

At Steven’s funeral, Marie was still in shock, it seemed. Witnesses said she stood by the grave in a daze. Shortly afterwards, Beth took her aside and told her that she was finally leaving Frank, and that she and Marie would be moving to Florida together. Marie seemed incredulous. “You had this plan all along to take me to Florida?” she asked.

When Beth told her yes, that she’d found a job there, Marie seemed to have a hard time breathing. At the time, Beth thought it was just the shock of so many things happening at once.

In Florida, the idyllic life Marie had imagined with just her and her mother didn’t materialize. Marie was so depressed that some days she couldn’t get out of bed. Beth sent her to a counselor, but it didn’t seem to do any good.

Then, that summer, Frank arrived on Beth and Marie’s doorstep. He wanted to patch things up with Beth, promising to change and work harder on their marriage. Beth, against Marie’s protests, took him back.

But — in a twist that should surprise no one — only weeks later, Marie found a note on his pillow from another woman. Beth said Marie told her, “Mom, you can put up with him if you want to, but I don’t have to. I miss Texas, and I’m going home.” So Beth contacted Marie’s other grandparents, Steven’s father and step-mother, and arranged for Marie to go live with them back in Fort Worth.

Once again in a new high school, Marie nonetheless excelled, making straight A’s, playing on the volleyball team, and working on the yearbook staff. Even though she was quiet and reserved, her classmate Stacey High was immediately drawn to her. Coming from an abusive background herself, Stacey recognized the signs that Marie was trying to hide something. So Stacey reached out to her, and before long, the two were best friends.

Despite the two being nearly inseparable, Stacey could never get Marie to talk about her dad. It was the same at home with her grandparents: Marie refused to go to his gravesite and would leave the room if he was mentioned.

About halfway through their senior year, Marie and Stacey were working on their English homework: reading Hamlet. Stacey recalled reading King Claudius’ soliloquy in Act III, the one that begins:

“O, my offence is rank it smells to heaven;

It hath the primal eldest curse upon’t,

A brother’s murder. Pray can I not,

Though inclination be as sharp as will:

My stronger guilt defeats my strong intent;…”

Stacey said that upon hearing the soliloquy, Marie’s face went white, and her hands were trembling. “Stacey,” Marie asked, “Do you think people can go through life without a conscience?”

Stacey said she responded, “Well, how about the kind of person who can look somebody in the eye and kill him in cold blood?”

At that, Stacey said, Marie got up from the table where they were studying and backed up against the wall, crumpling to the floor in tears.

Stacey asked Marie what was wrong. Marie answered with a question: What was the worst thing she could think of?

Stacey, a typical teenager, immediately thought Marie was pregnant. But that wasn’t it. After a few guesses, Stacey jokingly asked, “You didn’t kill somebody, did you?”

Marie broke down in sobs. “My father,” she said. “I poisoned him.” She told her that she’d stolen some barium acetate from chemistry class and slipped it into her father’s refried beans the night he died.

Marie then swore Stacey to secrecy.

Stacey, for her part, tried to keep her best friend’s secret. But she began being haunted by nightmares of Marie chasing her, or of Steven calling to her from the grave. Her mental health deteriorated; she started drinking and “partying too much” to try and distract herself from her guilty secret.

At one point, she told her mother. But Stacey’s mother thought that Marie had just made it up because she was distraught over her father’s death. The few close friends she confided in said the same thing. Stacey said she had a complete mental breakdown, and ended up checking herself into an outpatient mental-health facility.

After several weeks of this torment, Stacey couldn’t take it anymore. She finally went to the school counselor and told her to call the police about Marie. In order to corroborate Stacey’s story, the Fort Worth police would have to test Steven’s blood for barium acetate. Luckily, they were able to get his preserved tissue samples just days before they were set to be destroyed. The hard part was finding a lab that had the proper equipment to test for barium acetate: a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer, a machine that costs about $150,000. It took them nearly four months to find a lab with the proper equipment, all the way in Pennsylvania. Then it took another several months before the results came back.

In the meantime, Stacey and Marie graduated and went on to college — Marie, to the University of Texas at Austin; Stacey, to Sam Houston State University in Huntsville. Marie, who was studying to become a medical pathologist, paid her tuition with the $60,000 life insurance money left to

her by her father.

While waiting on the lab’s results, Fort Worth police did some investigating on their own. They went to the high-school chemistry classroom where Marie had attended while she was living with her father. There, they found barium acetate. They also found a safety manual with pages for each of the chemicals listing safety precautions, toxicity amounts, and what to do in case of accidental poisoning. The page for barium acetate was missing. When the tests came back showing Steven had 28 times the lethal amount of barium acetate in his body, police went to Austin to arrest Marie. She surrendered without incident.

Once inside the station, she very quickly confessed to what she had done. When asked why, she said it was because she had wanted to go and live with her mom again. She was released on bond, and using the insurance money, retained a pair of veteran defense attorneys. Their strategy was to claim that Marie didn’t know the chemical would kill her father; she had only wanted to make him sick. That claim didn’t hold up under any scrutiny. First, Marie was an excellent chemistry student — she knew exactly how lethal barium acetate was. She had even taken the page out of the school’s chemical safety manual so she could insure her own safety while poisoning her father with it. On top of that, if she only wanted to make her father sick, how would that help her go live with her mother? But perhaps most damning was the fact that when her father was lying on his floor, writhing in agony while the paramedics tried to save him, she had said nothing.

On May 9, 1996, after deliberating only an hour, the jury came back with its verdict: guilty of one count of first-degree murder. At her sentencing hearing, she cried and repeated how sorry she was, but was still sentenced to 27 years in prison. Behind bars, she was a model inmate. In 2003, after serving only seven years of her sentence, she was released on parole. She has since married and taken her husband’s last name.

Strangely, there are many — including Steven’s parents — who have sympathy for Marie. They see her as a good girl who just “made a mistake,” despite the meticulous planning involved and her years of hiding her crime. Others point to her apparent regret and sorrow over her actions as proof she isn’t really a cold-blooded killer.

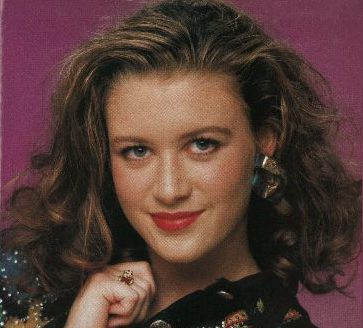

While I can understand those perspectives, I also can see that there are many other prisoners in Texas prisons and all over the country, who are sentenced to — and serve — much longer sentences for much lesser crimes. I suppose not having a big insurance fund to cover the cost of a good attorney could be a big factor in that. But I also can’t help but wonder if Marie Robards hadn’t been a pretty white girl, would she have gotten as much sympathy and forgiveness?

Much of this information comes from the excellent reporting in “Poisoning Daddy.”

-by DeLani R. Bartlette Sept 9 2019

Kathy Pinna

Kathy Pinna

Kathy Pinna

Kathy Pinna

Kathy Pinna

Kathy Pinna

Kathy Pinna

Kathy Pinna  Daniel Pinna

Daniel Pinna